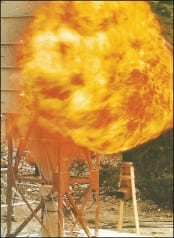

Dust in the chemical processing industries (CPI) is present in numerous operations, including powder processing; the transport of materials on belt or rotary-screw conveyors; grinding materials in giant shredders and pulverizers; machining, sawing, grinding or sanding operations; dumping bags of materials into reactors; handling coating materials; as well as the processing of pharmaceuticals and foods. An integral industry-safety issue arises when we consider the handling and suppression of the dust and particulate matter associated with these processes, namely preventing the formation of combustible clouds that can create a fire hazard or even trigger an explosion. Such a catastrophic dust explosion in a manufacturing facility is depicted in Figure 1. Additionally, protecting workers from the dangers of potentially dusty environments, including contact irritations and inhalation exposure, is an important factor in determining the methods and extent to which the particulate matter or dust needs to be suppressed or eliminated.

Regulations

Dust hazards are so problematic to employees that the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA; Washington D.C.; www.osha.gov) has implemented rules for personal protective equipment (PPE) — specifically dust masks and respirators, under standard 29CFR 1910.134 — to protect workers [1]. This standard states: “In the control of those occupational diseases caused by breathing air contaminated with harmful dusts, fogs, fumes, mists, gases, smokes, sprays or vapors, the primary objective shall be to prevent atmospheric contamination. This shall be accomplished as far as feasible by accepted engineering control measures (for example, enclosure or confinement of the operation, general and local ventilation, and substitution of less toxic materials). When effective engineering controls are not feasible, or while they are being instituted, appropriate respirators shall be used pursuant to this section.” It goes on to state: “A respirator shall be provided to each employee when such equipment is necessary to protect the health of such employee. The employer shall provide the respirators, which are applicable and suitable for the purpose intended. The employer shall be responsible for the establishment and maintenance of a respiratory protection program. The program shall cover each employee required by this section to use a respirator.”

Additionally, the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA; Quincy, Mass.; www.nfpa.org) has stepped in and set consensus standards, based upon good engineering practices, to control and prevent combustible-dust related hazards. NFPA 654 (Standard for the Prevention of Fire and Dust Explosions from the Manufacturing, Processing and Handling of Combustible Particulate Solids) applies to all phases of the manufacture, processing, blending, pneumatic conveying, repackaging and handling of combustible particulate solids or hybrid mixtures, regardless of concentration or particle size, where the materials present a fire or explosion hazard [2]. In addition to this standard, the NFPA has also set standards for specific industries and processes, such as: NFPA 61 (Standard for the Prevention of Fires and Dust Explosions in Agricultural and Food Products Facilities), NFPA 484 (Standard for Combustible Metals) and NFPA 664 (Standard for the Prevention of Fires and Explosions in Wood Processing and Working Facilities). These standards hold, as a top priority, the action of minimizing and controlling dust and particulate matter in processing industries from both a fire- and explosion-hazard safety standpoint.

In addition to the human-health impact, combustible airborne dust and particulates in the right environment — where confinement, dispersion, concentration, oxidants and ignition are present or potentially present — can create explosions. Combustible dust, according to both OSHA (CPL 03-00-008) and NFPA 654, is defined as a particulate solid that presents a fire or deflagration hazard when suspended in air or some other oxidizing medium over a range of concentrations, regardless of particle size or shape. The most common industrial sources of combustible dust include: food (such as candy, sugar, spice, starch, flour and feed), grain, tobacco, plastics, wood, paper, pulp, rubber, textiles, pesticides, pharmaceuticals, dyes, coal, metals (such as aluminum, chromium, iron, magnesium and zinc), and fossil-fuel power generation [3]. When these dusts are ignited, they can produce a fireball 8–10 times larger than the original volume of the cloud in the absence of confinement. Conversely, in a confined environment, explosive pressures can increase to as high as 8–10 times the original pressure.

Control measures

Every dust has unique physical and chemical characteristics that impact its level of hazard. Physical characteristics include size, shape and moisture content, among others. Chemical characteristics include flammability or combustibility, explosibility, susceptibility to thermal degradation and instability, susceptibility to ignition, and chemical reactivity. It should be noted that the physical characteristics of the dust also effect the chemical characteristics. For example, as particle size and moisture content decrease, the maximum explosion potential and maximum rate of pressure rise per unit time increases and the minimum ignition energy (MIE) generally decreases [4]. The dust-explosion hazardous classes (ST) range from 0 (no explosion potential) to 3 (very strong explosion potential). Testing of representative dust samples is the best method to classify dust materials. Typically, the cost of testing is recovered in reduced engineering-control costs.

To control dust and particulate matter, vacuum systems with various forms of filtrations and particle-removal devices have been designed and installed in industry. The engineering and design behind some of these systems can be very detailed and intricate. The key to their design is to move the dust and air at a velocity fast enough to keep the dust or particulate matter suspended and moving inside of transport ductwork until they reach the filter mechanism or cyclone separator. At this point, they are removed from the air to an acceptable level before the air is released back into the facility or outside environment.

These mechanical air-purifying systems are intended for removing dust and particulate matter. An important aspect to their function, besides proper design, is proper maintenance — specifically changing filters and keeping the system clean. This ensures that dust and particulate matter do not build up in the equipment and cause a hazardous fire and explosion scenario; this is the reason they were installed in the first place. In addition to proper design, the installation of explosion-protection (such as venting or suppression systems), explosion-isolation, and spark-detection systems may be required, depending upon the properties of the dust being collected. One might think this is obvious; however, systems installed to mitigate dust and particulate matter have historically been involved in fire and explosion incidents, as seen in the dust-collector explosion in Figure 2.

In some cases, dust is removed through a wet-scrubbing arrangement where the dust or air stream comes into intimate contact with water, and the dust is removed from the air stream. The dust may be dissolved in the water or may create a slurry. In either case, this type of collection requires further treatment of the water solution or sludge for environmental purposes.

In addition to vacuum-bag or filter systems, water and various polymer-additive systems have also been used to control dust, mainly in coal, mining and dirt-road applications. These systems typically consist of a water-only, water-polymer solution or oil-based liquid that is laid down or sprayed onto a surface by a nozzle-manifold or firehose-like system.

Avoiding incidents

Due to the number of incidents related to combustible dust — there have been 281 major events reported from 1980–2005, which have killed 119 workers, injured another 718 workers, and destroyed many industrial facilities [3,5] — OSHA reissued its CPL 03-00-008 Combustible Dust National Emphasis Program (NEP) on March 11, 2008. Although OSHA does not yet have its own standard pertaining to combustible dust, the agency cites combustible-dust hazards, including fire deflagration, explosion and related hazards under the General Duty Act of 1970. This act states that an employer shall furnish to each of his employees employment and a place of employment which are free from recognized hazards that are causing or are likely to cause death or serious physical harm to his or her employees [6], and relies on NFPA standards for the recognition of such hazards. This includes the statement that employers must furnish each employee with a place of employment that is free from recognized hazards that are causing, or are likely to cause, death or serious physical harm. In 2007–2009, OSHA conducted approximately 1,100 combustible-dust inspections and issued over 4,900 citations for both combustible-dust hazards and other safety violations. From these violations, the following list summarizes some of the General Duty Violations issued by the OSHA inspectors [7]:

• Dust collectors were located inside buildings that lacked proper explosion-protection systems, including for venting and suppression purposes

• The rooms with excessive dust accumulations were not equipped with explosion-relief venting distributed over the exterior walls and roofs of the buildings

• The horizontal surfaces, including those on beams, ledges and screw conveyors at elevated surfaces, were not minimized to prevent accumulation of dust

• Equipment, such as grinders, shakers, mixers and ductwork, were not maintained to minimize escape of dust into the surrounding work area. This becomes especially problematic when employees may have direct contact with powder or dusty materials, such as when pouring bags into reactors or vessels (Figure 3). Also, the employer did not prevent the escape of dust from the packaging equipment, creating a dust cloud in the work area

• Interior surfaces where dust accumulations could occur were not designed or constructed to facilitate cleaning or to minimize combustible-dust accumulations. Regular cleaning frequencies were not established for walls, floors and horizontal surfaces, such as ducts, pipes, hoods, ledges and beams

• Compressed air was periodically used to clean up the combustible-dust accumulation in the presence of ignition sources

• Explosion vents on dust collectors and bucket elevators were directed into work areas and not vented to a safe, outside location away from platforms, means of egress or other potentially occupied areas

• Process hazard analysis (PHA) was not conducted to determine whether the process hazards necessitated the installation of approved devices, such as explosion-protection systems, interlocked rotary valves, deflagration vents and flame-front diverters

• The employer did not provide adequate maintenance and design of dust-collector systems, which created insufficient air aspirations, low duct velocities and blocked ducts

Even with OSHA implementing the NEP program, combustible-dust related incidents continue to be a major industrial problem in the U.S. and globally. There were over 500 combustible-dust related incidents reported in 2011 in the U.S. alone [8]. That number does not include the events associated with grain elevators or coal-fired power plants, or smaller flash fires that were quickly extinguished, as well as other near-misses that failed to be reported.

From the above list, some good rules of thumb and generally accepted good engineering practices for facilities that contain dust and particulate matter from production are [9]:

• Implement appropriate engineering designs and controls to minimize the presence of dust and to prevent the dust explosion pentagon (Figure 4) from occurring

• Perform manufacturer-recommended maintenance on all equipment to ensure that it is functioning as designed

• Implement good housekeeping practices, including using surfaces that minimize dust accumulation, periodic inspections for hidden areas of dust accumulation and controlling sources that could cause dust to become airborne to maintain a clean, dust-free working environment

• Follow other measures, including: bonding of equipment to ground to control static electricity; controlling smoking and sources of open flames and sparks; managing friction and other sources for mechanical sparks

• Provide hazard recognition training for employees per OSHA 3371-08 2009

• Establish overall safe work practices, such as proper electrical-area classifications, physical barriers for the hazard, cleaning that does not generate dust clouds and locating relief valves away from dust

• Report and record any and all incidents or near-misses, as they are a valuable tool and resource for preventing larger, more serious incidents

With all these recommendations, regulations, reported incidents and near-misses, facilities should strongly consider use of competent personnel and knowledgeable individuals to provide testing, hazard assessments, risk analysis studies and engineered solutions to minimize or control dangerous dusts and particulate matter in manufacturing.

To achieve process-safety excellence, employees must be genuinely proficient and competent in their requisite technical disciplines, and appropriate levels of knowledge must be embedded in key positions throughout an organization with a mechanism for longevity. Or, put more simply, organizations must have “the right people, with the right skills, implementing appropriately designed process-safety programs, motivated by the right organizational culture, in the right way.” Results are far-reaching and broad, affecting finances, the environment and most of all, workforce safety. Properly managing dust protects the workforce, facility and the environment, while maintaining stakeholder confidence and encouraging compliance with all legislation and avoiding regulatory intervention. Eliminating or minimizing dust is a small investment compared to the costs of the harm that can occur if not appropriately addressed.

References

1. OSHA Standard 1910: Personal Protective Equipment, 1998–2011.

2. NFPA 654: Standard for the Prevention of Fire and Dust Explosions from the Manufacturing, Processing and Handling of Combustible Particulate Solids, 2013.

3. OSHA, Combustible Dust: an Explosion Hazard, OSHA website, https://http://www.osha.gov/dsg/combustibledust.

4. Amyotte, P., “An Introduction to Dust Explosions: Understanding the Myths and Realities of Dust Explosions for a Safer Workplace”, Elsevier, 2013.

5. U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board, Investigation Report: Combustible Dust Hazard Study, Report No. 2006-H-1, November 2006.

6. OSHA General Duty Act of 1970, Sec. 5 — Duties, 1970.

7. OSHA Status Report on Combustible Dust NEP, October 2009.

8. National Fire Incident Reporting System. (NFIRS) Combustible Dust Policy Institute, 2011 Combustible Dust Related Incidents Fact Sheet, April 2013.

9. OSHA, Combustible Dust in Industry: Preventing and Mitigating the Effects of Fire and Explosions, SHIB 07-31-2005.

Author

Walter S. Kessler is a senior process engineer and safety specialist at Chilworth Technology, Inc., a DEKRA Company (113 Campus Drive, Princeton, N.J. 08540; Phone: 609-799-4449; Email: [email protected]). He has 20 years of experience in process design, development and improvement, process control, logic-controller programming, process-hazard analysis, layers-of-protection analysis (LOPA), safety-integrity levels (SIL) and process safety management in petroleum refineries, gas and chemical plants, as well as pharmaceutical, manufacturing and wastewater facilities. Kessler holds a B.S.Ch.E. from Pennsylvania State University and is currently obtaining a Ph.D. at the University of Houston.