With the increasing demand for security, drums and other liquid vessels that contain valuable or hazardous liquids can be retrofitted with a simple dispensing-valve system that virtually eliminates leakage and ensures product integrity

Although the storage, security, handling and dispensing of both potentially hazardous and valuable liquids can present some measure of risk, these risks can be reduced through the use of appropriate security and safety-related systems and technologies. While the manufacture, transport and use of hazardous chemicals and related products are heavily regulated, there tends to be a “regulatory chasm” when it comes to the dispensing of such liquids, which is when accidents can occur. Mishaps due to improper dispensing procedures can result in the unintended loss of both hazardous and valuable products, creating significant short- and long-term risks and costs for facility owners and operators.

Chemical process facilities devise and implement site-specific programs to safeguard against contamination, pilfering, tampering, leakage or the fugitive escape of chemicals, solvents and other liquids. The method of dispensing from small containers, drums and intermediate bulk containers (IBCs) is often overlooked, however. With such diverse contents as specialty chemicals, industrial solvents, crop-protection products, mineral oils, edible oils, cleaning supplies, liquid detergents and other liquids that are hazardous to both worker safety and the environment, dispensing of these products needs the same consideration as liquids that are transported or contained in more highly engineered tanks, vessels and piping systems elsewhere in the facility.

This article discusses the use of a mechanical valve system that provides precise liquid-dispensing capabilities for drums and other storage vessels. Comprised of a relatively simple extractor valve, valve coupler and pump, the system ensures the safe and efficient transfer of liquids from drums and containers ranging in size from 5 to 330 gal. The use of such a closed liquid-dispensing system serves two important purposes; it not only protects workers and the environment from inadvertent exposure to the drum contents, but it also protects the drum contents from damage or spoilage resulting from the unwanted ingress of air, moisture and other contaminants. The various engineering considerations and long-term lifecycle-cost advantages that can be realized when drums, IBCs and other containers are outfitted with this mechanical apparatus, are summarized below.

Putting Controls in Place

In recent years, environmental and worker-safety standards and regulations have become increasingly stringent, and most industrial facilities are covered by a combination of local, state and federal regulations, compliance agreements and other required operating practices.

|

Additionally, in today’s highly litigious society, pollution-related liabilities often pose an enormous (and unpredictable) financial burden on companies that produce, store, handle, use and sell commodity and specialty chemicals, agricultural chemicals, pharmaceuticals, industrial solvents, and other potentially toxic, corrosive and otherwise hazardous liquids.

The desire to minimize the risk of liability and contain related costs has spurred many forward-looking companies to not only implement the technical controls needed to meet the prevailing requirements, but also to impose even stricter internal standards for their own operations, investing in advanced technology though no regulatory requirements force them to do so. Today, managers and corporate leaders must balance these objectives in the face of unrelenting pressure to control and justify all costs and operate in the leanest possible fashion. Because companies are often reluctant to spend money that offers no immediate or obvious return on investment, it is too often the case that, when it comes to drums, containers and IBCs, many operators opt to maintain the status quo instead of investing in appropriate technologies for dispensing hazardous or valuable liquids properly.

Such thinking is shortsighted, however, especially when one considers the many potential consequences that can result from inadequate or inappropriate attention to safe and secure chemical dispensing. For instance, when evaluating the potential costs associated with retrofitting a single drum or container, or an entire fleet, facility operators must weigh the initial and ongoing costs of the technology solution against the complete lifecycle savings that could reasonably be anticipated. Ample opportunities for direct savings and avoided costs arise from the use of proper dispensing technologies, especially considering that the improper dispensing of hazardous fluids from drums, containers and IBCs (and failure to correctly safeguard their contents) can have the following consequences:

-

Customer compliance issues resulting from an un-secure containment

-

Security issues arising after the security seal is removed

-

Worker exposure and workplace contamination

-

Losses associated with pilfering of valuable products

-

Environmental contamination

-

Increased costs related to downtime required for cleanup

-

Increased risk of slip and fall injuries

-

Increased fire- and explosion-related risks due to vapor release

-

Increased potential for liability, litigation and workers’ compensation claims

-

Increased risk of regulatory penalties and negative publicity

-

Increased maintenance requirements and parts replacement, as a result of fouling and corrosion

-

Spoilage or contamination of container contents, as a result of the unwanted ingress contaminants

Business as Usual

Considering that most types of chemical packaging must undergo United Nations/Dept. of Transportation (UN/DOT) certification to ensure that the container contents can be transported and stored safely, it is somewhat ironic that many industrial employees and factory workers still rely on the time-worn “tip and pour” approach when dispensing the liquids from 55-gal drums and smaller containers.

Using such an approach, several workers simply hoist the drum (which can weigh as much as 700 pounds when full), open its closure and pour out its contents as needed. Such a simplistic and imprecise approach invites numerous problems, ranging from lift-related physical injuries, to chemical exposure, to liquid spills that can lead to slips and falls. And while personal protection equipment, such as overalls, respirators, boots and gloves, are typically available at such facilities, they are often not used in places where drums and IBCs are handled.

Meanwhile, attempts to meter the dispensing of the contents using a conventional tip-and-pour approach often lead workers to simply jam something into the opening in order to slow or increase the flow erratically. Similarly, simple gravity-dispense valves offer little control of the metering process and are prone to leakage around the gaskets if improperly installed.

In other instances, a so-called “stinger” or “dip-tube” arrangement is used, whereby a drum pump attached to a hose is dropped into the drum through the open bung. In this case, the ladings are readily exposed to environmental contaminants, and the package security is permanently breached. Once the contents have been dispensed, the hose and pump apparatus is pulled from the drum, allowing the stinger tube to become contaminated. Futhermore, drum fluids vaporize into the air and potentially splash or drip onto workers and the floor, creating a variety of safety and liability issues.

A Simple Upgrade

The closed liquid-dispensing valve system discussed here is a simple technology that has three major components: an extractor valve, a coupler, and a pump (Figure 1). The extractor valve seals the drum by screwing into the opening of the drum or IBC, using a threaded connection. The valve has a “dip tube” that travels from the bottom of the valve to the floor of the container.

Figure 1. This closed liquid-dispensing system utilizes an extractor valve, a coupler and a pump. A cutaway image of

the valve coupler in a container is shown

The security-keyed valve coupler is connected to the top of the valve, once the valve has been installed in the drum opening. When the valve is engaged by the use of a coupler, the contents are extracted from the bottom of the container through the dip tube, and are allowed to flow out through the valve. The extractor valve opens and closes when the user engages and disengages the handle on the coupler, and an external pump is then used to remove liquids from the drum.

The final component of the system is the pump that extracts the liquid (Figure 2). Pump selection is made considering several site-specific factors, including the need for dosing versus transfer applications, required flowrates, chemical compatibility issues, voltage requirements, and whether self-priming capabilities are a requirement.

Figure 2. Selection of the pump that extracts liquid in a dispensing system is determined by site-specific factors

Such a closed liquid-dispensing system can be used to control both the filling of the container and the dispensing of its contents. Two inherent design features of the apparatus help to further assure worker safety and guard against the unintended loss of drum contents. First, the spring-loaded extractor valve in the stainless-steel system must default to a closed position, providing failsafe operation against unwanted liquid loss and overriding the potential for operator error. Second, the valve system should have a “dry-disconnect” design, so that when the coupler is disconnected from the valve, less than two milliliters of residual liquid is left on the wetted parts.

Various tamper-evident devices can be installed, which is especially important during drum refilling and recertification, ensuring that only “like product” may be put back into a given container.

In standard applications, these systems can be used as open/closed dispensing valves for straight liquid transfer into the process line. However, when the drum contents must be delivered in precise, metered amounts, the closed liquid-dispensing system can be connected to various pumps, flowmeters or venturi-type volumetric measuring devices.

Material Concerns

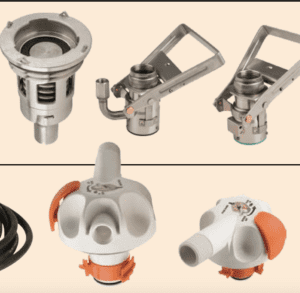

Closed liquid-dispensing valve systems are available in two basic materials: stainless steel (for use in mild steel, plastic drums and IBCs), and plastic (specifically HDPE, for use in plastic drums and IBCs). Steel and plastic components are shown in Figure 3. In general, the material is selected as a function of its compatibility with the liquids it will encounter in the drum or IBC.

Figure 3. Stainless steel (above; valve, coupler, coupler) or plastic (below; valve,

coupler) components are chosen based upon their compatibility with the liquid being handled

The plastic HDPE valve and coupler components have wide chemical compatibility, making them suitable for a broad range of chemical applications, while the stainless-steel components are typically reserved for applications requiring long life and durability.

Closing Thoughts

The initial investment required to upgrade and modernize new drums, containers and IBCs — and retrofit existing ones — with closed, dry-disconnect dispensing valves can provide rapid return on investment (see box above). Direct payback comes from reducing the risk of unintended fluid losses, ensuring product and vessel security, reducing the spoilage of valuable raw materials, process aids and finished products, and making the dispensing workplace safer. These improvements can provide a direct bottom-line impact for the business owner, helping the facility to operate more competitively over the long run.

Experience from the FieldAs noted in the main text, the relatively small investment required to install or retrofit drums and IBCs with closed liquid-dispensing valves — rather than threatening profitability goals — provides direct operational advantages and demonstrable cost savings. Two recent examples help to showcase some of these benefits. Eliminating the risk of chemical cross contamination. West Central, Inc. (Willmar, Minn.; www.westcentralinc.com) is an agricultural chemicals distributor that sells a wide range of crop-protection products, such as pesticides and insecticides, herbicides, fungicides and a full range of surfactants, oils, chemical enhancers and other additives to retailers and agricultural coops, which then sells them to end users. West Central routinely repackages chemicals from its suppliers, supplying them in reusable drums of stainless steel and polypropylene, ranging in size from 15 to 300 gal. Once the contents have been drained by the end user, the drums are returned to West Central for periodic cleaning and refilling. “One of the biggest challenges in the agricultural chemical business is the risk of cross-contamination as drums are returned for cleaning, reconditioning and refilling,” says Randy Mogard, warehouse manager and purchasing agent for West Central. “The accidental application of even one ounce of an Ag-chem product that was not intended could end up killing hundreds and hundreds of acres of valuable crops.” About seven years ago, West Central began to retrofit its 12,000-vessel fleet with a closed, liquid-dispensing valve-coupling system, and today, about 90% of the company’s drums are outfitted with the valve assembly. “Using this mechanical device, it’s completely impossible to backfill the wrong product through the valve, so this eliminates all possibility of cross-contamination,” says Mogard. A typical Ag-chem drum used by West Central has a 7- to 10-yr life expectancy, and prior to using the new valve assembly, the company had been using a “rather typical pumping and extraction setup,” says Mogard, whereby a hose and pump was dropped into the drum and a power unit was mounted on top. “This was not only messy for operators in our repackaging facility, but it did not provide a true closed system to protect workers from exposure to the pesticides and insecticides, and ensure product integrity,” he notes. Making matters worse, while West Central’s drums enjoy a long life expectancy, “we typically had to rebuild or replace this crude pumping and extraction system every year — at a cost of about $100 each time (or more than $700 over the life of each drum) — because certain components had many moving parts, while others would deteriorate from prolonged exposure to the chemicals in the drums,” says Mogard. By comparison, in the seven years since West Central has been using the new valve systems in its drums, “we’ve never had to change a valve,” he adds. “Once every two years or so, we replace the seal that is used to ensure a snug fit between the valve and the threaded connection, since these are most susceptible to damage from the drum contents.” At just $3 per seal, these savings quickly helped the company to justify its initial investment in the closed liquid-dispensing valve systems. Safe handling of chlorinated solvents. Safe-Chem Europe GmbH (Düsseldorf, Germany; dow.com/safechem), a Dow Chemical Co. subsidiary, is a leading supplier of chlorinated solvents (perchloroethylene) for the dry-cleaning industry. To ensure the safe management and efficient transfer of its solvents during use, the company supplies them in specially designed storage containers, shown above, which are constructed from 304 or 316 stainless steel with a polyurethane outer layer to protect the inner stainless-steel container from damage. Spent solvents are collected by the user and periodically sent for recycling (to a third-party waste-management company) in specialized versions of these containers that have a double-walled, stainless-steel construction. Since 1996, all of these storage containers for chlorinated dry-cleaning solvents have been equipped with dry-disconnect, quick-release, closed liquid-dispensing valves as well as a solvent-vapor-return coupling, and an overfill protection device. “Using the vapor-return coupler, the solvent can be transferred from the containers to the machinery with virtually no risks of emissions or spills,” says Ferdinand Pree, SafeChem’s technical manager. “The product will not be released until the coupler and the valve are securely connected, and this makes unauthorized refilling of the container impossible,” says Pree, who notes that the dry-disconnect feature, which guards against unintended spills and fugitive emissions losses, provides added protection to workers and the environment, and reduces solvent waste, during solvent dispensing. The average service life of both the container itself and the valve system is 20 years, according to SafeChem, requiring only a seal replacement, about every six to eight years. Edited by Kate Torzewski |

References

|

AuthorsHenrik Rokkjaer is the general manager for Micro Matic USA, Inc, Industrial Div. (667 Spice Island Drive, #101, Sparks, NV 89431, Phone: 775-356-0555; Email: [email protected]). Rokkjaer received his B.S. in mechanical engineering from the Technical College of Odense (Denmark). Before joining Micro Matic, Rokkjaer was a tool shop supervisor at Meneta A/S. Joining Micro Matic in 1992, he served as a tool-and-die engineer, moving on to become a project engineering manager in 1995, and a project engineer at the U.S. headquarters the following year. In 2000, he obtained his current position. Bryan Gran is the vice president of sales for Micro Matic USA, Inc., Industrial Services, North America (19791 Bahama St., Northridge, CA 91324, Phone: 818-882-8012; Email: [email protected]). Gran received his B.S. in animal science from the University of Nebraska (Lincoln, Nebr.). He held a position as a sales representative for Dow Chemical Co., before joining Micro Matic USA in 1992 as director of sales, Industrial. In 1999, he became president of Integrated Packaging Services, and has held his current position since 2007. |