When paired with deep process expertise, cost estimation becomes a powerful tool for mitigating risk and guiding investment for large capital projects

Chemical manufacturing is one of the most complex and capital-intensive industries in the world. From specialty chemicals to large-scale commodity production, projects involve high-pressure systems, hazardous materials and stringent regulatory standards. In this environment, accurate financial planning is not optional, it is essential. Cost engineering provides the discipline to forecast, plan, and control project expenditures throughout their lifecycle.

Cost overruns, timeline delays and unpredictable returns continue to challenge capital projects in the chemical process industries (CPI). To mitigate these risks, forward-thinking companies are turning to structured cost engineering, supported by robust estimating standards and process expertise. This article explores how engineers can ensure that their cost estimates are effective to deliver predictable outcomes in chemical manufacturing, enabling alignment between investment, performance, scalability and sustainability.

Why is cost engineering important?

Unlike many industries, the CPI require projects that must operate reliably under extreme conditions while meeting exacting product specifications (Figure 1). A well-developed cost engineering scheme will provide a full picture of total cost of ownership — from initial process feasibility testing, through piloting and capital expenditures, and including operations and maintenance.

FIGURE 1. Complex equipment configurations, along with extreme volatility in material pricing and demand, contribute to the challenges of accurate cost engineering in chemical industry projects

Key trends influencing costs in the CPI today include the following:

- Decarbonization pressure: Growing demand for low-carbon technologies

- Feedstock volatility: Raw material pricing unpredictability

- Energy transition: Shift to renewables and electrification

- Digitalization: AI-driven analytics reshaping design and forecasting

This confluence of scenarios creates unique cost drivers, such as:

- High capital expenditure (CAPEX) requirements for process equipment, including mechanical vapor recompression systems, distillation towers, heat-recovery interchangers and specialized materials

- Complex operational expenditure (OPEX) considerations due to variations in feedstock volatility, utility demand and waste-treatment needs

- Regulatory compliance dictating best practices surrounding safety, emissions and environmental impact

Considering all of these factors into their cost engineering enables chemical producers to meet environmental, social and governance (ESG) targets, qualify for green financing and future-proof their operations.

Even modest deviations in cost estimates can lead to overruns that jeopardize profitability. According to industry reports, 60–70% of large chemical projects face cost overruns, primarily due to poor scope definition, inadequate early-stage estimating, inflationary supply-chain disruptions and regulatory permitting delays [1].

Structured cost engineering, early engagement with expert consultants and technology-driven decisions can help to mitigate these challenges. Such engineering rigor ensures cost estimates are not just accurate, but actionable and aligned with process deliverables.

Original equipment manufacturers (OEM) will employ processes and procedures that drive cost, risk and improvement opportunity discussions that can be reused as a vehicle to quantify project risks, as well as drive business decisions. Similar processes can be used at the manufacturing plant level for all types of projects. The methodologies are transferrable. Quantitative models should form the backbone and the bulk of cost estimation for chemical production equipment. Qualitative tools are equally critical in ensuring estimates reflect both commercial viability and project risk. Two structured approaches — the bid-no-bid (BNB) process and the risk and opportunity matrix (ROM) — illustrate how qualitative judgment can be systematically converted into measurable cost impacts.

BNB process. This initial screening, typically conducted by the sales or commercial engineering team, applies a structured framework to evaluate whether an opportunity merits pursuit. The framework is organized around the following four considerations:

- Can we add value? — Measures and (where possible) quantifies business impact and project drivers

- Should we pursue? — Considers relationships, technical expertise, geography, schedule and preliminary risk

- Can we compete? — Examines competitive offerings and positioning

- Alignment – Evaluates engagement with decision-makers, executive sponsorship and strategic fit

ROM. For projects that advance beyond the BNB stage, the ROM provides a more detailed risk assessment. This tool evaluates potential exposures across several dimensions, including: technical and process performance, commercial terms and conditions, resource availability, scope of work and schedule and geographic and political considerations. The ROM converts qualitative concerns into quantifiable risk costs. For example, if a performance guarantee is identified as a risk, the potential financial impact of underperformance can be estimated, mitigation strategies defined and mitigation costs allocated. The residual risk is then expressed as a percentage and integrated into the project budget.

This approach ensures that qualitative judgment directly informs cost-estimation theory, creating more realistic, risk-adjusted project budgets and improving decision-making confidence.

Project de-risking

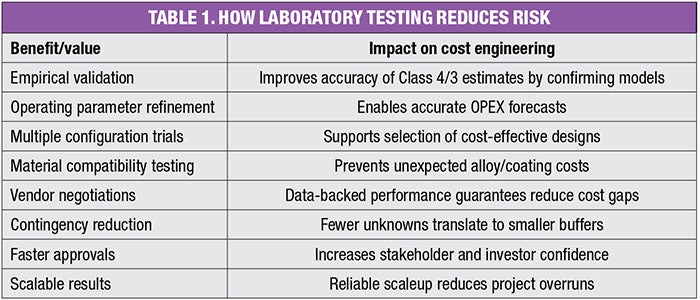

Every capital project carries uncertainty, whether it be due to feedstock behavior, separations performance, fouling and foaming potential, scaleup risks, energy consumption or general operability. An opportunity for project de-risking is the utilization of testing centers, pilot plants or laboratories where processes can be validated under realistic conditions. Such test centers can often support multi-million-dollar projects for chemical manufacturers, helping secure contracts by providing empirical proof of feasibility. Table 1 summarizes some of the de-risking benefits of tying physical project validation with cost estimation.

Strategic role of cost estimation

Cost estimates are utilized to ensure that projects are selected based on an accurate rate of return, based on CAPEX, OPEX and regulatory requirements. Chemical manufacturing involves complex unit operations, including distillation, crystallization, solvent recovery, evaporation and heat recovery and are designed to process hazardous or high-value compounds under controlled conditions. Projects are often large-scale, capital-intensive, and highly regulated, leaving no room for error in budgeting.

A robust cost-engineering strategy ensures that capital and operating expenditures are forecasted, tracked and optimized throughout a project’s lifecycle. This discipline supports:

- Feasibility evaluation and project screening

- Budgetary planning and investment approvals

- Vendor and contractor bid evaluations

- Risk management through contingency development

- Lifecycle economic analysis (return on investment, net present value and payback time)

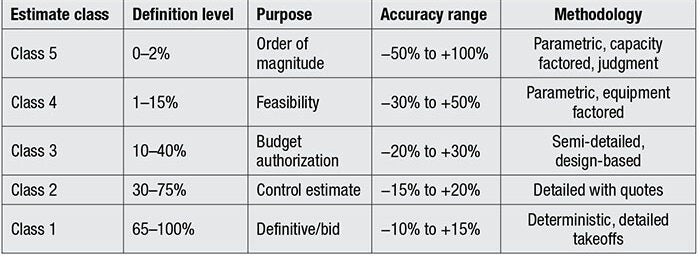

Cost estimates can be classified by the level of project definition. While accuracy ranges are helpful to visualize phases, accuracy does not necessarily determine class (only the level of scope definition does), nor does class directly define accuracy, since accuracy is result of risk analysis, which will be unique for every estimate).

Estimate classes are commonly used across the chemical, process, and heavy industrial sectors, and examples of some accuracy ranges developed by the authors are given in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Such classifications allow owners, engineers and investors to match the right estimating method with the right project stage, balancing the need for accuracy with available information.

Parametric cost estimating

In the context of early-stage (Class 5 or Class 4) construction-cost estimating, parametric refers to using mathematical relationships between key project parameters (such as equipment capacity, plant size or throughput) and historical cost data to estimate overall project costs.

Rather than detailing every component, a parametric estimate applies cost-per-unit metrics (for instance, $/gallon of capacity, $/square foot or $/kW of power) based on similar past projects.

Parametric estimating is especially useful during feasibility studies, when detailed design work hasn’t yet been completed but decisions must still be made about project viability.

Cost engineering in action

By combining process engineering with rigorous cost estimation, engineering teams can go beyond simple projections and deliver actionable roadmaps for success. By employing cost-engineering best practices at every project phase, project managers can feel secure in both technical excellence and financial predictability. Consider, for example, a mid-sized specialty chemicals producer with the objective of improving product recovery and reducing emissions of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from a solvent recovery and purification system.

Step 1: Class 4 feasibility estimate. The engineering team developed process alternatives and performed equipment-sizing studies based on simulations. A Class 4 estimate was issued to±40% accuracy. The business case projected a 2.5-year payback.

Step 2: Class 3 budget estimate. Detailed process flow diagrams (PFDs) and piping and instrumentation diagrams (P&IDs) were developed (typical industry recommended practice for Class 3 estimates dictates that P&IDs are complete during this phase). The team prepared a budget-level estimate, including vendor request for quotations (RFQs), instrumentation rough-ins and mechanical installation allowances.

Step 3: Class 2 control estimate. Equipment was specified and competitively quoted. Subcontractor bids were solicited. The estimate included labor productivity factors and a final control budget.

Outcome. The final installed cost was within 3% of the Class 2 estimate. Operating costs dropped by 18%, emissions were reduced by over 30%, and the client achieved a return on investment (ROI) 9 months ahead of schedule.

Best practices

In chemical manufacturing, financial success begins with precise technical scope and accurate cost forecasts. Cost engineering, when executed with discipline and domain expertise, transforms complex capital projects into manageable investments. In summary, some best practices for maximizing value from cost estimates include:

- Preliminary process-viability testing

- Early-stage cost modeling (Class 5/4 feasibility and screening)

- Process simulations tied to capital forecasts

- Detailed cost takeoffs (Class 3 to 1) with real-time vendor pricing

- Constructability-informed contingency modeling

References

1. Singh, S., Sadara: Lessons Learned, The Chemical Engineer, Sept. 2018.

Authors

David Loschiavo (Email: david.loschiavo@rcmt.com) is the general manager of RCM Thermal Kinetics, where he leads the company’s strategic direction and oversees engineering innovation and business development. With more than 25 years of experience in pilot testing, R&D, process design engineering and technical sales management, he has guided numerous projects from concept through full-scale commissioning. His expertise spans distillation, evaporation, crystallization and modular plant design, with a focus on advancing high-efficiency process systems for the chemical and renewable-fuels industries.

David Loschiavo (Email: david.loschiavo@rcmt.com) is the general manager of RCM Thermal Kinetics, where he leads the company’s strategic direction and oversees engineering innovation and business development. With more than 25 years of experience in pilot testing, R&D, process design engineering and technical sales management, he has guided numerous projects from concept through full-scale commissioning. His expertise spans distillation, evaporation, crystallization and modular plant design, with a focus on advancing high-efficiency process systems for the chemical and renewable-fuels industries.

Kelly Carmina, P.E. (Email: kelly.carmina@rcmt.com) serves as proposal manager at RCM Thermal Kinetics, an engineering and equipment firm specializing in evaporation, distillation and crystallization technologies. With over 25 years of experience in the chemical and industrial sectors, she guides projects from research and development through pilot and commercial scale. Her consulting background, coupled with her experience in heat- and mass-transfer equipment manufacturing, enables a comprehensive approach that integrates process, mechanical and control considerations with effective project costing, planning and execution.

Kelly Carmina, P.E. (Email: kelly.carmina@rcmt.com) serves as proposal manager at RCM Thermal Kinetics, an engineering and equipment firm specializing in evaporation, distillation and crystallization technologies. With over 25 years of experience in the chemical and industrial sectors, she guides projects from research and development through pilot and commercial scale. Her consulting background, coupled with her experience in heat- and mass-transfer equipment manufacturing, enables a comprehensive approach that integrates process, mechanical and control considerations with effective project costing, planning and execution.