The troubleshooting methods described here can help engineers to understand operational realities when “running blind” in complex distillation processes

One of the most critical aspects in ethanol production is the distillation unit. Distillation processes are vital for recovering ethanol from water and removing other impurities. When issues arise in these operations, they can lead to decreases in production rate, efficiency and product quality. This article explores troubleshooting techniques to address issues in a distillation unit. The techniques can also be utilized in other processing units.

When any distillation system is designed, the heat and mass balance (HMB) is established, and the new equipment is often oversized, because safety factors are incorporated to “guarantee” that the unit will be sufficiently robust to meet process demands. Sizing and specification of equipment related to the distillation process, including vessels, heat exchangers, pumps, control valves and instrumentation, and their integration with piping, are generally performed by separate subject matter experts or vendors, who often do not fully appreciate the nuances of the other pieces of equipment that they have not specified.

Troubleshooting any process unit, however, requires a different approach. The individuals undertaking this effort must have a working understanding of how the equipment, controls and piping work together as a collective unit. The troubleshooter does not necessarily have to be an expert on all individual pieces of equipment, but must have a working knowledge of the major components and understand how the individual components interact with one another.

The key to effectively troubleshooting a system is to recognize how the system components relate to one another. This article describes the exercises undertaken to correct an underperforming ethanol distillation system.

Ethanol distillation

The heart of the fuel-ethanol purification process is the distillation of the fermented mixture. The mixture, often referred to as “beer,” is heated in a distillation unit where the ethanol, water and other components are separated due to their different boiling points. Ethanol has a lower boiling point than water, so it vaporizes at a lower temperature. To complicate matters, ethanol and water form an azeotrope, a mixture of two or more components that has a constant boiling point and whose vapor has the same composition as the liquid in equilibrium with it.

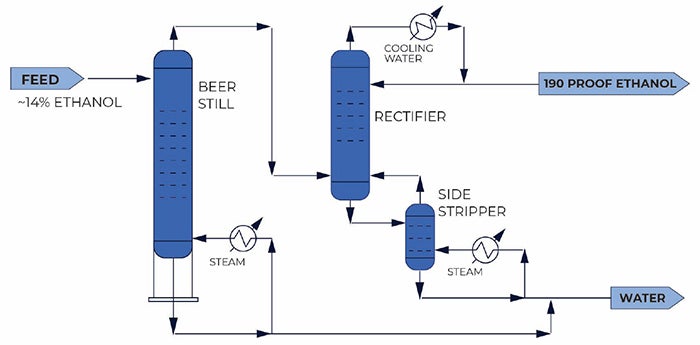

Often, the distillation process is broken into two towers — the beer still and the rectifier. Typically, the feed mixture, which contains ethanol, water, other components (such as fermentation byproducts like fusel oils) and solid materials from the fermentation process, is fed to the top of the beer still (which often contains fixed valve trays). These types of trays can help to improve reliability and enhance fouling resistance. The beer still is driven by the reboiler, the main heat source for the distillation process. As the mixture is heated, the stripped water and non-volatile materials flow to the sump, and ethanol vapor rises through the beer still. See Figure 1 for a typical fuel-ethanol distillation system.

FIGURE 1. A typical distillation system for fuel ethanol often contains three distillation towers

The vapor from the beer still flows to the bottom of the rectifier, where the ethanol is purified to approximately 190 proof (95%) as it approaches the azeotrope composition with water. The hydrous ethanol composition from the top of the rectifier is adjusted based on the amount of reflux that flows back to the top of the rectifier.

Common distillation issues may include poor separation efficiency, foaming and off-specification ethanol purity. To overcome poor separation efficiency, the distillation column must be properly designed and operated, with capabilities for monitoring the temperatures and pressures at various stages. This helps to identify inefficiencies and pinpoint which operating parameters must be adjusted, such as the amount of heat and reflux provided to reduce the amount of ethanol lost in the bottoms and to improve quality of the hydrous ethanol distillate, respectively. Foaming or flooding issues can also hinder the separation process, so proper column operation must be evaluated, and mass and heat transfer equipment designs that hinder tower performance must be avoided.

Troubleshooting approach

Today, conducting meetings via online communications platforms is the new normal. However, to troubleshoot a distillation unit, or any other unit for that matter, it is the obligation of the engineer to visit the job site to conceptualize the system, including its equipment, instrumentation, controls and piping arrangement. Also, there is no substitute for face-to-face discussions with operations personnel, since they have a distinct perspective and greater appreciation for the unit’s limitations. Operators, who are uniquely involved with the plant, learn to live with and work around the challenges that may be the result of operational changes not configured into the original design basis. Plant operators often know the real unit limitations.

During the design phase of a project, the development of heat and material balances, equipment sizing, instrumentation and controls selection and piping layout are often performed by different departments. Because of this, there may be process disconnects among the different disciplines with regard to how the individual system components will work together.

When troubleshooting a unit, a practical approach involves collecting actual field-operating data. Troubleshooting engineers must arm themselves with key documentation before attempting to gather field data to maximize performance of the unit. At a minimum, these items include the process flow diagrams (PFDs) and piping and instrumentation diagrams (P&IDs). Having knowledge of the major component designs (for instance, distillation column internals, heat exchanger capabilities, pump capacities and so on) is also a requirement.

Troubleshooting a distillation unit requires integrating specific process knowledge and general process engineering skills. The unit’s heat balance drives the distillation system, especially as energy efficiency and lower-carbon intensities take center stage in plant operations. In an integrated system, where a portion of a tower’s overhead vapor is used to drive the separation of the other tower and provide heat in another part of the plant, it is imperative that the process flowrates and heat balance are understood to effectively troubleshoot the unit.

The process design engineer must know that the heat input to a distillation tower is equal to the energy taken out of the tower, while accounting for any changes in the system’s internal energy ( Q), if any exist. The key components of the heat balance around the distillation column include:

- Inlet streams — feed and steam

- Outlet streams — products and cooling water

- Sensible heat for each stream

- Latent heat when phase change occurs

- Internal heat generated or absorbed due to reactions or other factors

- Energy balance — Qin = Qout + Q internal

Real-world troubleshooting

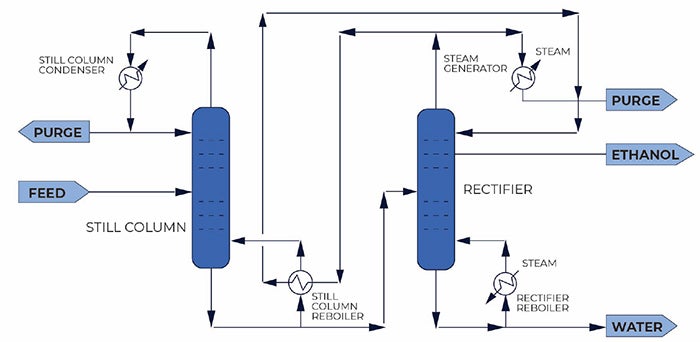

The troubleshooting examples detailed in this article concern a distillation unit located in the U.S. that produces about 25 million gal/yr of high-quality ethanol. The unit comprises, in part, a still and rectifier. The purpose of the unit is to produce ethanol that only contains trace amounts of fusel oils (for example, isoamyl alcohol, isobutanol, propanol, butanol and hexanol) and other “bad actors,” which may include different aldehydes, organic acids, esters and ketones. Fusel oils and some bad actors (such as acetaldehyde) accumulate in the distillation columns, interfering with ethanol-water separation.

Feed is introduced to the middle of the still, where its distillate is made up of a small slip stream of ethanol with volatile bad actors, and sent off to be reprocessed through the fuel ethanol unit. The wet ethanol and remaining fusel oils become the still’s bottom product, which is then pumped to the middle of the rectifier. The rectifier produces a light purge stream containing fusel oils, 190-proof ethanol side product and process water from the bottom.

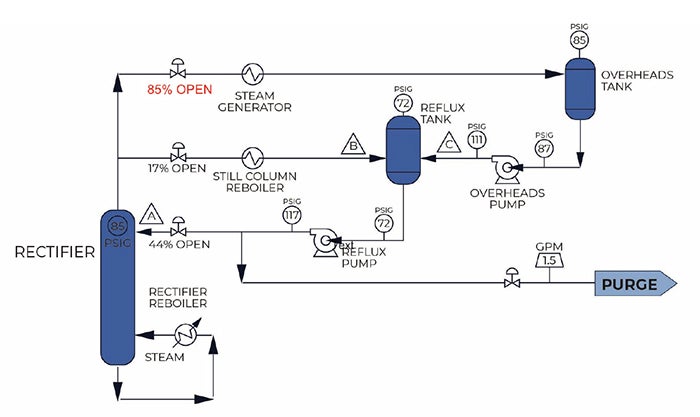

The distillation unit is driven by utility steam that flows to the rectifier reboiler. The overhead vapor from the rectifier column is split into two streams, where half of the vapor is flow-controlled to a steam generator to produce low-pressure steam. This steam is used in the fermentation process. The remaining vapor is used to drive the separation in the still through its reboiler. See Figure 2 for a sketch of the distillation unit being described.

FIGURE 2. The troubleshooting examples shared in this article stem from the high-quality ethanol distillation process illustrated here

The engineering contractor who was tasked with executing the overall plant design, which included specifying, procuring, installing and calibrating the instruments and developing the distillation unit’s piping design, was unable to resolve operating issues and high differential pressures in the still during startup, even though flow instruments in the unit were providing values lower than the design outputs for steam, reflux and overhead vapors.

Over the next five months, instrument technicians visited the site on multiple occasions to recalibrate flow instruments. In addition, the engineering contractor and its engineering consultant visited the facility multiple times in hopes of determining the root cause of the still’s overpressure scenario at design conditions. The engineering contractor initially surmised that the column’s trays were flooding at the design rate, potentially due to excessive foaming or a deficiency in the tray design. To investigate the cause of the elevated pressure drop, a tower gamma scan was conducted at what were believed to be normal design operating conditions in order to evaluate the internal hydraulic behavior of the column.

A tower gamma scan employs a controlled radioactive source that emits gamma radiation through the vessel. Detectors positioned externally around the column measure the attenuation of the radiation as it passes through the tower and interacts with the internal process fluids. By analyzing the intensity of radiation detected at various elevations, an internal hydraulic profile of the tower can be developed, providing insight into liquid holdup, froth height and phase distribution across the trays.

Interpretation of the scan data indicated clear variations in liquid and vapor distribution throughout the column. The column was constructed with 34 trays at 24-in. tray spacing. Beginning at the top tray, it exhibited about 5 in. of froth, representing a relatively light hydraulic load. The next three trays below it showed froth heights corresponding to roughly 50 to 60% of tray spacing. Moving further down the column, the following seven trays demonstrated significantly higher froth levels, on the order of 70 to 85% of tray spacing.

Below this point, the bottom 23 trays exhibited conditions consistent with jet flooding. In this region, there was no discernible separation between vapor and liquid phases above individual trays, indicating excessive vapor velocity. Jet flooding is an abnormal operating condition in which high vapor rates increase spray height and entrain liquid from one tray to the tray above, severely degrading separation efficiency. Under normal operation, trays typically perform best between 15 and 80% of jet flood.

The gamma-scan results confirmed that the still was experiencing severe flooding at design throughput. The critical question, however, remained unanswered: what was driving the flooding under conditions that were assumed to be within the original design envelope?

Instrumentation and controls

Technicians attempted to calibrate flow instruments on multiple occasions after commissioning. The flow instruments and valves of greatest concern for the stable operation of the distillation unit were the following:

- Rectifier reflux – vortex meter

- Still reflux – vortex meter

- Steam to rectifier reboiler — Annubar (a flowmeter type that employs the averaging pitot tube measurement principle)

- Rectifier overhead vapor to still reboiler — Annubar type

- Rectifier overhead vapor to steam generator — Annubar type

- Rectifier overhead vapor-control valves to still reboiler and steam generator (identical)

The output from the steam flowmeter to the rectifier reboiler was unreliable due to improper installation. Thus, heat input to the distillation unit was unreliable. In addition, the rectifier overhead vapor rates to both the still reboiler and steam generator were also inaccurately measuring flow, because the conditions for upstream and downstream straight-run lengths of pipe required for proper operation were not met. Similarly, the selection of the vapor control valve for the still reboiler did not fully consider the downstream system pressure and valve size to properly regulate flow. Finally, still and rectifier reflux rates reported by the control system were faulty due to improper instrument calibration, as will be explained further in this article.

Instrumentation troubleshooting

Because values from many of the unit’s flow instruments were untrustworthy, a new troubleshooting approach was undertaken. This time, an engineer who had not been involved in equipment design or commissioning of the distillation unit and had no preconceived notions of what was limiting the unit’s processing capabilities was sent to the site. The approach was simple — seek the truth from the operating equipment via the following measures:

- Assuming all flow instruments were unreliable, except for the feed and product Coriolis meters which, by law, are required to provide accurate readings

- Operating the unit at steady-state and gathering sufficient field data to establish the unit flowrates

- Using the field data and regressed historical data (such as pressures and temperatures) to establish a process simulation model

This approach relied on performing a pressure survey of the unit by gathering actual operating data from the distillation unit. These data included:

- Suction and discharge pressures for the operating pumps

- Pump motor nameplate data

- Pump motor amperage readings

- Control valve positions

- Operating pressures of reflux and overhead vessels

Prior to starting the pressure survey, a walkdown of the distillation unit was performed to assess the piping arrangement and valve positions for hydraulic considerations, and to establish the locations and elevations where pressure readings would be taken. This is typically the most efficient and reliable approach to performing a pressure survey.

To maintain consistent pressure readings, feed to the distillation unit was set at 52 gal/min, the rate at which the unit was able to operate stably and produce on-specification products. Also, steam feed to the rectifier reboiler was held constant. Valve positions were noted in the field, and motor amperage-draw measurements were taken for all operating pumps in the unit. It took less than four hours to gather the necessary field data to troubleshoot the unit.

By using the gathered field measurements, the exercise to establish entire circuit hydraulics, including feed, products and internal flows (such as reflux) was straightforward. To supplement the gathered field data, historical data from the distributed control system (DCS) were provided, including temperatures during the period when the pressure survey was conducted.

Because the still experienced high pressure drops and flooding at “assumed” design rates, determining the root cause was imperative. Flooding in a distillation column can be caused by various factors, and it is crucial to identify and address them. Below are some potential causes of flooding in a distillation column:

- High vapor velocity, which can often lead to increased liquid entrainment in the vapor

- Excessive liquid flow exceeding the tray’s capacity, which can cause backup

- Mechanical damage to trays, which disrupts their performance

- Foaming, which may prevent proper liquid draining

Pump total dynamic head

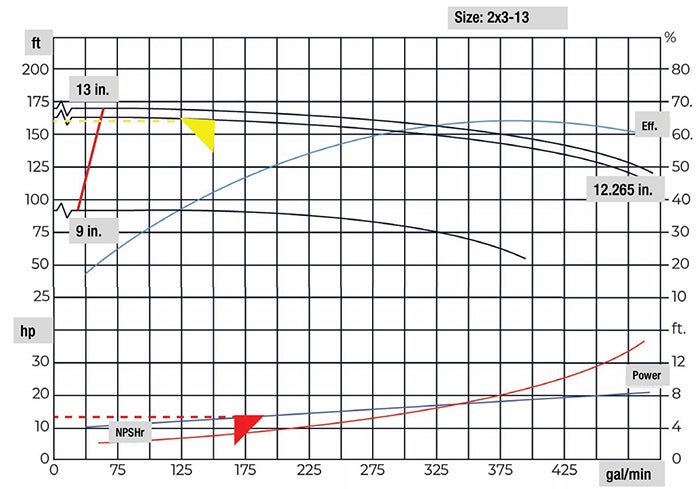

The still reflux flowmeter consistently read 97 gal/min, but its design rate was about 200 gal/min at a design feed rate of 62 gal/min. To determine if this was correct, the still reflux pump’s total dynamic head ( TDH) was calculated using Equation 1:

TDH = ΔP x 2.31/SG (1)

where:

ΔP = PDischarge – PSuction, psi

2.31 = 2.31 ft of water column = 1 psi of differential pressure)

SG = Specific gravity

The field pressure measurements for the suction and discharge were 14 psig and 65 psig, respectively. The specific gravity of the fluid was 0.72. Based on this information, it was determined that the pump’s TDH was around 164 ft. Based on the pump curve in Figure 3, the corresponding flow was approximately 167 gal/min (indicated by the yellow triangle in Figure 3), or 72% more than the flowrate indicated by the reflux flowmeter (97 gal/min).

FIGURE 3. This pump curve shows the performance of the still reflux pump

Pump motor amperage

Valuable equipment details, such as pump motor information from equipment nameplates, were gathered during the walkdown of the unit. A typical pump-motor nameplate contains information such as horsepower, phase, efficiency, power factor and so on.

To determine if the still’s reflux flowmeter or its pump’s TDH was a better indicator of the actual flow, the pump’s motor amperage reading was used to determine its working horsepower (HP). During the pressure survey, the motor voltage was 460 V and its amp reading was 14.5 A. Using the motor nameplate information gathered during the walkdown, its efficiency (93%) and power factor (0.84) were noted. It is a three-phase motor using a 460-V connection, so Equation 2 was used.

HP = [V x A x E x PF x Ph½] / 746 (2)

where:

HP = Working horsepower

V = Volts supplied to the motor, V

A = Amperes drawn by motor, A

E = Motor efficiency

Power Factor (PF) = Dimensionless number between 0 and 1 that is the ratio of true power (kW) to apparent power (kVA); this is typically found on the motor nameplate

Ph = Number of motor phases (typically a three-phase motor)

746 = Constant for converting watts to horsepower (746 W = 1 hp)

The still reflux pump’s motor-power output was calculated at 12.1 hp, which corresponds to a flow of about 172 gal/min, as noted by the red triangle in Figure 3. As with the pump’s TDH, the corresponding flow using the motor HP is about 77% higher than the reflux flow meter (97 gal/min). The corresponding flows using the pump TDH (167 gal/min) and the motor’s working HP (172 gal/min) were comparable to one another.

The results of the still reflux pump TDH and its motor HP provided corroborating evidence that the actual reflux flow was much higher than the rate indicated by the reflux flowmeter, confirming that the reflux flow instrument was unreliable. In a distillation column with a trivial amount of distillate and constant feed and bottoms flowrates, its reflux is almost directionally proportional to the amount of heat input to the column. In other words, the higher reflux rate requires a higher heat input. As a side note, when the technician was subsequently called to recalibrate the instruments again, it was discovered that the wrong specific gravity was previously used.

Control valve

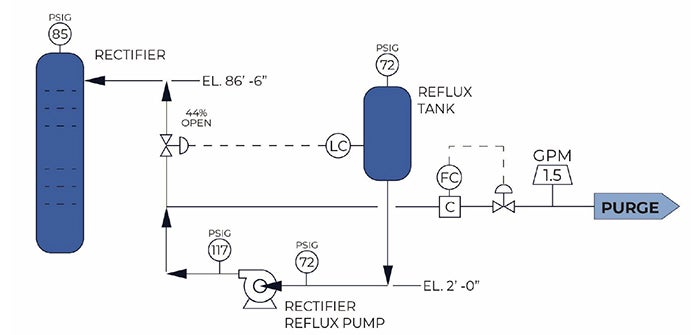

Valve flow coefficient (Cv) is a measure of a valve’s capacity for fluid to flow through it relative to the pressure drop across it. A sketch of the rectifier reflux circuit is shown in Figure 4. The reflux is composed of 190 proof ethanol. There was no reflux flowmeter installed, so the methodology to determine the reflux flowrate involved using its control valve datasheet and field data gathered during the pressure survey, including pressures, valve opening percentages and elevations.

FIGURE 4. The rectifier reflux circuit included a critical control valve that was used to help determine the reflux flowrate

During the pressure survey, the valve was open 44%, and its corresponding Cv was 33.7. The fluid’s specific gravity was 0.68 and the valve’s ΔP was 35 psi. Based on the gathered field data, the calculation to determine rectifier condensate from the steam generator was around 241 gal/min using Equation 3:

Q = Cv (ΔP/SG) ½ (3)

where:

Q = Flowrate, gal/min

Cv = Valve coefficient (determined experimentally for each style and size of valve)

Rectifier reflux

To determine the rectifier reflux flow, a hybrid process was used. Because the rectifier reflux pump curve was relatively flat over the operating range being considered, its motor amperage was used to calculate the working horsepower using Equation 2, which was then used to determine its corresponding flowrate. To validate the flow, the rectifier reflux control valve position and its upstream and downstream pressures taken during the pressure survey were then used to determine the valve’s corresponding Cv, differential pressure and resultant flowrate using Equation 3. The rectifier reflux flow was determined to be 445 gal/min.

Process simulation

With the distillation unit’s pump TDH and motor amp readings, and suction and discharge-pressure control valve data from the survey, a process simulation model was developed for the system. It provided clarity on the true heat and mass balance of the unit during the test run. The simulation results confirmed that the heat input to the rectifier was much higher than the steam flowmeter indicated, and correspondingly, the rectifier overhead vapor flowrates to both the still reboiler and steam generator were much higher than indicated by their respective flowmeters.

Design rate

The pressure survey and its simulation confirmed that most of the flow instruments in the distillation unit were erroneous. However, the unit was designed for a feed rate of 62 gal/min, so the feed was increased accordingly. Previously, when feed was increased to above 52 gal/min, the still experienced a high pressure drop due to jet flooding. A decision was made to manually operate the control valve in the rectifier overhead vapor line going to the still reboiler to stabilize the vapor flow and keep the still trays from flooding. The vapor control valve was adjusted by the experienced operator. The vapor flow was so sensitive to the control valve opening that a 0.1% increase in valve output was enough to flood the column if not kept in check. The distillation unit was allowed to come to steady state and on-specification samples were taken after about 24 hours of stable operation. The design feed rate was maintained, the still was kept from flooding and product samples were on-specification.

The system meeting the final purity and throughput requirements was severely delayed due to poorly calibrated flow instruments, improper flowmeter location and incorrect control-valve selection, all of which provided erroneous operating data and poor process control. The distillation unit, which for months struggled to meet its full capacity, finally met its expectations.

If the still and its reboiler worked well at the design flowrate, what caused the tower to flood? The answer was found in the rectifier overhead system.

Figure 5 depicts the rectifier overhead system. The control valves in the overhead vapor streams are identical in size and selection. However, hydraulic calculations and control valve selection were performed by a contracted piping design firm who also performed the piping layout so vital process data was lost in translation. The assumption that the pressure drop through both circuits was equal failed to consider the difference in destination pressures. The identical control valves operated on opposite ends of their performance curve. The control valves were designed for 1 psi pressure drop; however, the vapor through the steam generator circuit operated at less than 1 psi pressure drop, while the pressure drop through the reboiler circuit was more than 10 times that. This led to a major control failure.

FIGURE 5. The rectifier overhead system contained two seemingly identical control valves that were not properly calibrated

Control valves

Since control loops operate over a narrow throttling range, small signal changes to the control valve result in small valve stem movements. However, a small position change by an oversized valve can often give a larger-than-desired change in flow. Depending upon the accuracy of the elements in the loop, the control system then responds to correct the situation, which can result in a throttling sequence that oscillates back and forth, causing continuous variation in process conditions. Such was the case with the rectifier overhead vapor driving the still reboiler.

A valve gives the best control when it is sized to operate below 80% open at maximum required flow and not less than 20% open at minimum required flow. Using a larger-than-necessary valve compromises its performance. An incorrectly sized control valve will often result in problems. As seen in Figure 5, both vapor valves were operating outside the maximum or minimum desired range. In the case of the still reboiler, when the rectifier overhead-vapor control valve was manually set at 17.0%, the still could operate steadily. However, if the valve opening increased by approximately 0.1% or more, the still flooded soon thereafter. An indicator of an oversized valve is when a 1% change in controller output causes a greater than 3% change in the process. This was certainly the case in the control valve that was driving the still reboiler.

Flow instruments

Unreliable flow measurements were a major hindrance for proper operation of the distillation unit. During the unit walkdown, the location of the flowmeters measuring the rectifier overheads to the still reboiler and steam generator were observed to be erroneous, contributing to the unreliable operation of the distillation unit. Generally, there should be at least ten pipe diameters upstream and five pipe diameters downstream of the flowmeter to ensure a fully developed flow profile, reducing measurement inaccuracies due to turbulent flow patterns.

The solution

Cheap, quick fixes often fall short of their desired results. To ensure proper and predictable operation of the distillation unit, the following were the required modifications:

- Replace the oversized control valve in the rectifier overhead vapor to the still reboiler with a smaller valve appropriately sized for the circuit hydraulics

- To ensure proper vapor flow indication, relocate the Annubar flowmeters to meet the minimum piping requirements to avoid turbulent flow patterns

- Properly calibrate the vortex flowmeters in reflux services

The traditional compartmentalized design approach used by many engineering firms for new plant construction often results in longer-than-necessary commissioning and startup times, leading to production loss and engineering overruns. An alternate approach is to integrate the heat and material balance, equipment design and instrument and control specifications into process-flowsheet modeling. Although there are limitations to the commercial process models available, this approach is less costly. ■

Acknowledgement

All figures provided by author

Author

Roy Viteri is business development manager and senior process engineer at RCM Thermal Kinetics (Email: roy.viteri@rcmt.com; Website: www.rcmt.com/thermalkinetics). Viteri has extensive experience in the areas of heat and mass transfer, field troubleshooting and revamp design. His professional experience includes 37 years in process engineering in the chemical, refining and other industries.

Roy Viteri is business development manager and senior process engineer at RCM Thermal Kinetics (Email: roy.viteri@rcmt.com; Website: www.rcmt.com/thermalkinetics). Viteri has extensive experience in the areas of heat and mass transfer, field troubleshooting and revamp design. His professional experience includes 37 years in process engineering in the chemical, refining and other industries.