The latest NFPA standard applies to many industry sectors, and aims to address the fragmented nature of the industry-specific standards currently in place

On September 7, 2015, the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA; Quincy, Mass.; www.nfpa.org) issued NFPA 652 (Standard on the Fundamentals of Combustible Dust) [ 1 ]. There were already several industry-specific NFPA standards for minimizing hazards associated with the handling of potentially combustible dust and fine particulate materials. However, these individual standards do not always align, and the presence of numerous, competing standards creates confusion among operators, and increases risk at chemical process industries (CPI) facilities.

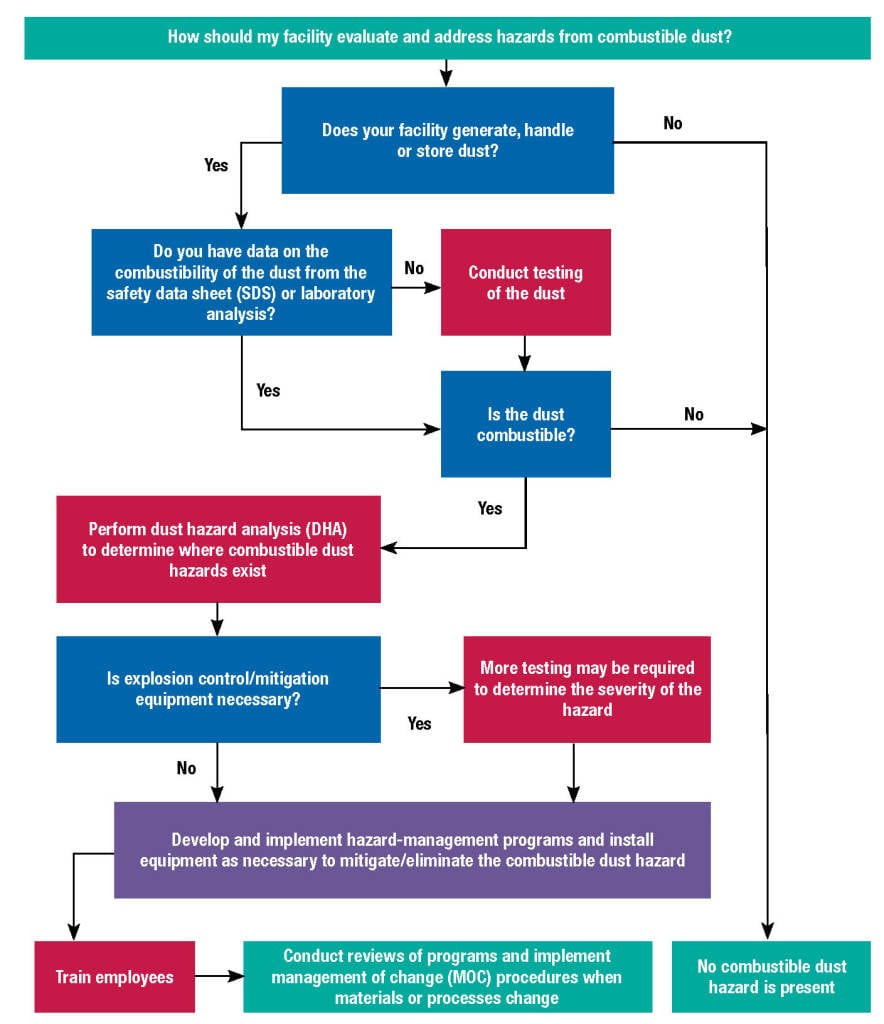

The publication of NFPA 652 is the first step toward creating a single, unified combustible-dust standard that would apply to all facilities that handle potentially explosive dusts (Figure 1). In addition, NFPA has also stated that, through its Combustible Dust Correlation Committee, the group plans to reformat some of the current NFPA standards so they become more aligned with NFPA 652.

NFPA 652 is still in its infancy, and as with all NFPA standards, it will continue to be improved and developed during future revision cycles. This article provides an update on the ongoing activities by NFPA, and discusses what is currently included in the new NFPA 652 Standard.

Figure 1. This decision-tree flowchart provides guidance for faciity operators, as they assess potential hazards associated with the handling or production of powdered materials that could be potentially flammable or hazardous under the right conditions

Fundamentals of dust hazards

Flash fires and explosions resulting from potentially combustible dust are responsible for a significant number of industrial accidents. However, the potential for dust-related flash fires or explosions is often overlooked. The serious hazards associated with handling fine dusts and powdered materials may be overlooked by many plant personnel because they are not fully understood.

The Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA; Washington, D.C.; www.osha.gov) has begun to increase awareness of the hazards associated with cobustible dust through its National Emphasis Program (NEP) [ 2 ]. The NEP often cites NFPA standards for combustible dust, as the NFPA standards have been written explicitly to both reduce the risk of a combustible dust incident, and minimize the hazards in the event of a flash fire or explosion. However, as noted, many of NFPA’s existing standards related to dust-explosion hazards are industry-specific. For example, wood processing and woodworking facilities would refer to NFPA 664, while food-processing plants that handle flour and sugar (both of which are potentially combustible solids under the right conditions), would refer to NFPA 61. Often, the different NFPA standards directed at specific industry segments do not align with each other, creating confusion.

NFPA 652 aims to consolidate all of the various combustible dust standards, in order to create a single, overarching standard that addresses fire and explosion hazards associated with combustible dust of all types, in all industries. NFPA 652 lays the groundwork for a standardized format that all NFPA regulations relating to combustible dust will use. The new standard also implements methods that all facilities can use to evaluate and control hazards associated with potentially combustible dust. During the transition period (while NFPA is working on updating some of the current standards to align with NFPA 652), facilities should ensure that they are in compliance with both NFPA 652 and any applicable industry-specific NFPA regulations that pertain to their operations.

What is included in NFPA 652?

NFPA 652 was created to apply to “all facilities and operations that manufacture, process, blend, convey, repackage, generate, or handle combustible dusts or combustible particulate solids” [ 1 ]. In addition to the general requirements listed in the standard, NFPA 652 also directs you to any applicable industry-specific standards that would apply to different facilities. Over time these earlier, industry-specific standards will become more aligned with NFPA 652.

The primary focus of NFPA 652 is to help all facilities to identify where hazards exist due to the presence or handling of combustible or potentially explosive materials. In order to do this, a qualified person will need to conduct a dust hazard analysis (DHA). To conduct a DHA, a facility will need to develop a sampling plan to coordinate the collection and analysis of dust samples throughout the facility. This will allow the facility to identify and evaluate areas where combustible dust hazards exist.

Once all potentially hazardous areas and process equipment have been identified and a DHA has been completed, the facility should work to reduce the likelihood of a flash fire or explosion from occurring. It should also implement procedures or equipment to mitigate the hazards associated with a combustible dust fire or explosion.

If possible, the facility should work to contain and collect combustible dust, by both preventing fugitive dust from being discharged from equipment and by installing an effective dust-collection system throughout the process areas that handle combustible dust. The facility should develop a management system that monitors how hazards relating to combustible dust are being controlled.

Facilities should also provide training to employees and contractors. Such training should focus on both general safety regarding the hazards associated with combustible dusts, and on any job-specific training relating to their specific work environments.

Hazard identification and DHA

NFPA 652 includes procedures that all facilities can follow in order to identify areas where potential combustible-dust hazards exist. Dust samples should be collected from throughout the facility (Figure 2), in order to determine the combustible or potentially explosive qualities of the dust. To carry out such sampling, all facilities are required to create a plan that should include the following [ 1 ]:

- Identification of locations where fine particulate materials and dusts are present

- Collection of representative samples

- Methods to ensure preservation of sample integrity

- Communication with the test laboratory regarding proper sample- handling procedures

- Documentation of samples taken

- Safe sample-collection practices

Figure 2. As part of the dust-sampling and hazard-assessment plan, it is important to collect representative samples of fine powdered materials that may be present in the facility. Keep in mind that fine particles are often found in elevated locations, such as ceilings, walls and ledges

Following a rigorous sampling plan will help facility operators to ensure that the dust samples are accurately analyzed to determine if they are combustible or potentially explosive.

Once dust samples have been collected and tested, if any of the materials are identified as being combustible or potentially explosive, the facility should then complete a DHA, to identify and evaluate the potential hazards associated with a fire or explosion due to the combustible materials handled throughout the facility. Inspections of areas where combustible dust is handled also allow facility operators to develop recommendations to minimize the risks of a combustible-dust incident.

Specifically, a DHA should include the following [ 1 ]:

- Identification and evaluation of locations or processes throughout the facility where hazards resulting from a potential fire, flash fire or explosion exist

- Identification and evaluation of specific fire and deflagration scenarios where fire and explosion hazards exist

- Identification of safe operating ranges

- Identification of any safeguards that are in place to mitigate the hazards of a fire or explosion

- Recommendations for additional safeguards, where needed

The DHA must be completed or led by a qualified person who has demonstrated the ability to understand combustible dust and associated hazards through education or experience [ 1 ]. This qualified person should inspect all buildings and processes to determine the potential likelihood of a fire or explosion due to the presence of combustible dust. This is determined by understanding the properties associated with the potentially combustible dusts that are handled in the building or process, identifying all potential ignition sources, and evaluating the effectiveness of any deflagration-suppression or protection systems that are currently in place.

Mitigating hazards

Once a DHA has been completed by a qualified person, the facility should begin to implement any recommendations made, to prevent or minimize the hazards. Often times, updated housekeeping procedures are the first actions facilities can take — for instance, to remove excessive dust accumulation in rooms and buildings (Figure 3). However, this requires extra labor and is often not as effective as expected.

Figure 3. While housekeeping is important, facilities should focus on containing and collecting potentially flammable or explosive dust from the processes that handle or generate fine powdered materials. These include such common, seemingly innocuous materials, such as sugar, flour and sawdust

For example, certain inaccessible areas (such as upper levels, rafters, beams and roofs) may not be inspected or cleaned often enough. Additionally, some housekeeping activities, such as cleaning dusty areas with compressed air, may pose additional (sometimes significant) hazards, as potentially combustible dust clouds are able to form in the areas that are being cleaned. Finally, housekeeping activities are often reduced or overlooked during periods of increased production or decreases in staffing.

Perhaps more importantly, facilities should make it a priority to take steps to contain and collect dust and powdered materials from the processes that handle or generate them. While conducting the DHA, facilities should try to identify any equipment where fugitive dust is being released into the work environment. Particular focus should be put on such systems and components as pneumatic and mechanical conveyance lines, sifters and screeners, bins and silos, dryers and cyclones, hammer mills and grinders, and unloading bins and stations. Once the leaks have been identified, plant engineers should work to repair the equipment — to prevent fugitive dust from escaping from these systems and accumulating inside the facility.

Prevention and capture

It is not always feasible to prevent the discharge of fugitive dust into a room or building, so other means of protection or hazard mitigation should also be implemented to reduce hazards and mitigate the risk of fire and explosion. Specifically, NFPA 652 states that any building or room where a dust deflagration hazard exists should be protected using venting systems that comply with NFPA 68. Also, pneumatic conveyance systems must be equipped with deflagration protection or suppression systems that will prevent a flash fire from traveling throughout the conveyance system and connected equipment; details are spelled out in NFPA 69.

Exhaust air from equipment should only be directed outside and not into the room unless specific guidelines are met. Facilities should also ensure that all central vacuum systems are equipped with tools and attachments that are constructed of metal or static-dissipative materials, and that all vacuum hoses are properly grounded.

While facilities should focus on prioritizing dust collection and containment from their processes, it is also important to implement safe housekeeping procedures in areas where dust accumulation cannot be avoided. Sweeping and water washdown are allowed under NFPA 652, but compressed air cleaning should only be used if certain requirements are met (NFPA 652, Chapter 8.4.2.6), such as the use of pressure-reducing nozzles and ensuring that no ignition sources are present in the area.

All housekeeping procedures implemented by the facility should be documented, and all employees and contractors should be trained on these procedures. Employee training should also include information regarding required personal protective equipment (PPE) to be worn during housekeeping operations, as well as instructions and training on how to properly use all equipment. In addition, the facility should ensure that all hot work being done onsite complies with NFPA 51B. The areas where hot work is being done must be cleaned before beginning the hot work, and all equipment in the area should be shut down.

NFPA 652 also states that facilities should conduct an assessment of workplace hazards, according to NFPA 2113, in order to determine if flame-resistant (FR) clothing is required. FR clothing is designed to not ignite when it comes into contact with a flame. If the assessment indicates that FR clothing is required, the facility must offer appropriate FR clothing to all affected employees.

Closing thoughts

NFPA 652 is the first step of many to consolidate and integrate a variety of NFPA standards that are intended to help reduce the risks for facilities producing or handling potentially combustible dusts and fine powdered materials. This new standard requires that all facilities create a sampling plan to test fine powdered materials from different locations and equipment, in order to determine if it is combustible or potentially explosive. If any of the dust samples pose a combustible dust hazard, a qualified person must conduct a DHA to determine how likely it is that a combustible dust incident will occur in a room or piece of equipment by evaluating the dust. Hazards assessments such as this are carried out by identifying any ignition sources, and evaluating any protection or suppression systems that have been implemented. Once the DHA has been completed, the facility should work to prevent or minimize the hazards. The facility should repair any leaks in equipment where fugitive dust is released into the work environment, and deflagration protection or suppression systems should be installed on at-risk equipment. Safe housekeeping procedures should be developed, and the facility should ensure that all employees and contractors have been trained.

While there is still a lot of work to be done by the NFPA dust standards committees, facilities throughout the CPI should begin to familiarize themselves with the new NFPA 652 standard, to be in compliance with the new standard. It cannot be stated strongly enough that CPI facilities must work aggressively and consistently toward minimizing the risk of combustible dust fires and explosions wherever fine, powdered materials are produced or handled.

Edited by Suzanne Shelley

References

1. National Fire Protection Association, “NFPA 652: Standard on the Fundamentals of Combustible Dust – 2016 Ed.,” Sept. 7, 2015; Accessed at: www.nfpa.org/codes-and-standards/document-information-pages?mode=code&code=652

2. Occupational Safety and Health Association (OSHA), “Combustible Dust National Emphasis Program (Reissued),” March 11, 2008; Accessed at: www.osha.gov/OshDoc/Directive_pdf/CPL_03-00-008.pdf

Authors

Christopher Frendahl is an environmental engineer with Conversion Technology, Inc. (2190 N. Norcross Tucker Rd, Norcross, GA 30071; Email: cfrendahl@ conversiontechnology.com). His professional work involves carrying out combustible dust hazard evaluations, implementing hearing-conservation and noise-study programs, and implementing industrial hygiene and industrial safety programs. Frendahl holds a B.S. in mechanical engineering from Georgia Tech.

Christopher Frendahl is an environmental engineer with Conversion Technology, Inc. (2190 N. Norcross Tucker Rd, Norcross, GA 30071; Email: cfrendahl@ conversiontechnology.com). His professional work involves carrying out combustible dust hazard evaluations, implementing hearing-conservation and noise-study programs, and implementing industrial hygiene and industrial safety programs. Frendahl holds a B.S. in mechanical engineering from Georgia Tech.

Brian Edwards, P.E., is director of engineering for Conversion Technology, Inc. (Same address as above; Phone: (770) 263-6330, ext. 103; Email: bedwards@ conversiontechnology.com). Edwards holds a B.S. in in civil and environmental engineering from Georgia Tech. He is a licensed professional engineer with more than 15 years of experience as a consultant to industry. As a member of the National Fire Protection Association, he is a Principal on the committee for NFPA 61, the standard for dust fire and explosion prevention in the agricultural and food processing industries. He has also worked with the Fundamentals of Combustible Dust technical committee on NFPA 652 – the overarching Standard on Combustible Dust.

Brian Edwards, P.E., is director of engineering for Conversion Technology, Inc. (Same address as above; Phone: (770) 263-6330, ext. 103; Email: bedwards@ conversiontechnology.com). Edwards holds a B.S. in in civil and environmental engineering from Georgia Tech. He is a licensed professional engineer with more than 15 years of experience as a consultant to industry. As a member of the National Fire Protection Association, he is a Principal on the committee for NFPA 61, the standard for dust fire and explosion prevention in the agricultural and food processing industries. He has also worked with the Fundamentals of Combustible Dust technical committee on NFPA 652 – the overarching Standard on Combustible Dust.

Jeff Davis, P.E., is senior engineering manager for Conversion Technology, Inc. (Same address as above; Phone: (770) 263-6330, ext. 116; Email: [email protected]). Davis holds a B.S. in chemical and biomolecular engineering from Georgia Tech. He is a licensed professional engineer with more than 10 years of experience as a consultant to industry. He is a member of the American Institute of Chemical Engineers (AIChE), and the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA). He has extensive experience conducting combustible dust hazard analyses (DHAs), process hazard analyses (PHAs), and designing fire- and explosion-protection systems at diverse facilities in a number of industries, including: chemical manufacturing, food processing, lumber and wood products, metal forming, and automotive and aviation parts.

Jeff Davis, P.E., is senior engineering manager for Conversion Technology, Inc. (Same address as above; Phone: (770) 263-6330, ext. 116; Email: [email protected]). Davis holds a B.S. in chemical and biomolecular engineering from Georgia Tech. He is a licensed professional engineer with more than 10 years of experience as a consultant to industry. He is a member of the American Institute of Chemical Engineers (AIChE), and the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA). He has extensive experience conducting combustible dust hazard analyses (DHAs), process hazard analyses (PHAs), and designing fire- and explosion-protection systems at diverse facilities in a number of industries, including: chemical manufacturing, food processing, lumber and wood products, metal forming, and automotive and aviation parts.