The elements needed for excellence in a process safety program are known, but achieving top-level process safety performance requires sustained effort and focus

Efforts to achieve excellent process-safety performance at chemical process industries (CPI) facilities are nothing new [1]. Experience shows that sustained excellent process safety performance is difficult, but not impossible, with the appropriate effort and resources. Although the CPI collectively possess the tools and knowledge for excellence in process safety, putting those into practice in all areas and at all times is difficult.

For most companies, achieving sustained positive results in process safety requires continuous focus and dedication. Sometimes a single mistake or equipment failure can lead to catastrophic results. Humans make mistakes and equipment can fail at any time, but many mistakes can be prevented, or their impact anticipated and safeguarded against. Similarly, equipment can be designed appropriately and effectively maintained, and the impact of failures can be anticipated and safeguarded against.

Excellent process safety performance requires continuous effort to implement, sustain and improve effective process-safety programs [2]. Guidance on the design and implementation of process safety programs has been available for many years [3], and in theory, most companies now have the technical knowledge and capabilities to safely identify and manage process hazards and risks. After all, process safety regulations have been in effect for over 25 years, and industry guidance and resources are widely available. In the early 1990s, Trevor Kletz [4] expressed that “new” accidents rarely occur; rather, the same types of accidents are repeated and therefore, should be preventable. More recently, Dennis Hendershot [5] similarly stated that “We know how to improve process safety performance… We need to actually do what we already know how to do, we need to do it well, and we need to do it everywhere and all of the time.”

Yet despite this recognition, process safety performance concerns in the CPI unfortunately remain too common: serious and near-miss process incidents still occur too frequently due to ineffective process-safety programs or to the lack of recognition that a process safety program is needed. Serious process safety incidents can lead to (1) fatalities and serious injuries, (2) catastrophic property damage, (3) significant environmental harm, (4) critical business disruption, (5) business reputational damage, and, in some cases, (6) negative community impacts. For example, a petroleum refinery explosion [6] resulted in 15 fatalities, 180 injuries, and major facility damage (Figure 1). Serious incidents and frequent near misses highlight significant performance problems and the ongoing need to achieve better process-safety performance, despite the industry’s emphasis on incident prevention and continuous improvement efforts. This article discusses the requirements for sustaining effective process-safety programs to help achieve excellent process-safety performance.

Defining safety performance

The primary objectives of effective process-safety programs are to identify, evaluate and manage process hazards to help achieve excellent performance and ensure safe processes and facilities. But how should performance be defined? A basic definition of the term is as follows: “excellent performance prevents serious injuries and incidents.” However, there are two potential problems with this definition. First, injury and incident statistics may be mixed with personal safety statistics (such as lost-workday cases) that may not provide a clear view of process safety performance. For example, subsequent investigation [7] following the refinery explosion in Figure 1 found that “reliance on injury rates significantly hindered… the perception of process risk.” Second, injury and incident statistics are lagging metrics, representing events that have already occurred, rather than helping to identify problems before they can lead to more serious injuries and incidents (that is, leading metrics). Since serious injuries and incidents are hopefully infrequent, these indicators do not provide true measurement of how a process safety program is performing. The question is: are process safety systems working the way they should be on a day-to-day basis, or are there problems that may be leading to higher risks? And how would facility personnel know?

Figure 1. Sustained attention to process safety reduces the risk of disaster [1]

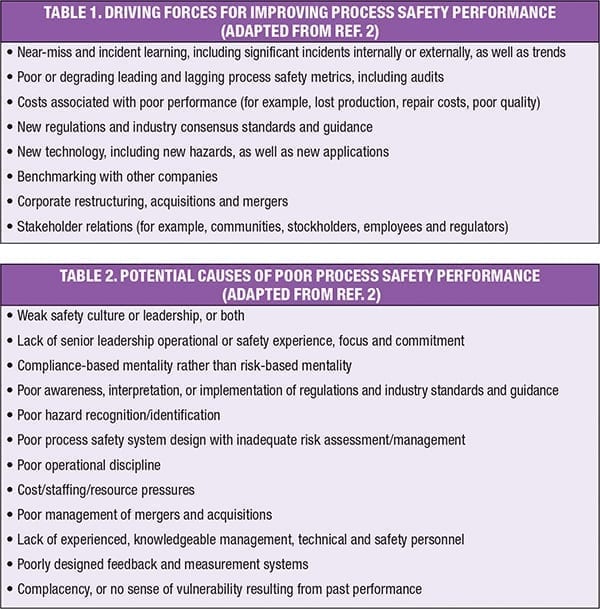

A better definition of performance relates to executing process-safety program requirements and systems with the intent of achieving program goals and objectives. Program goals should include the following: (1) how to prevent serious injuries and incidents related to process activities and (2) other leading and lagging indicators to measure the functionality and effectiveness of process-safety program activities to provide early warning of possible problems. Just as medical professionals measure vital signs, such as blood pressure and cholesterol levels, for early warning of potential health problems, accountable facility personnel should establish, monitor and respond to appropriate goals and metrics for process safety performance. For example, failing to document and assess changes to process equipment or to conduct equipment tests and inspections on the required schedules can greatly increase the risk of process-related injuries and incidents. Meaningful process-safety program goals with appropriate leading and lagging metrics, as well as management review of system performance, must be established to obtain a clearer view of process safety performance. How to achieve this is discussed here. While excellent performance can be demonstrated using lagging metrics, ultimately, excellent future performance can typically only be pursued using appropriate process-safety goals and leading metrics. Some important driving forces for achieving excellent process-safety performance are listed in Table 1, while potential causes of poor process-safety performance are listed in Table 2.

Current performance level

The key questions associated with process safety performance include the following:

- What is the current level of performance (high, average, or poor)?

- Is performance likely to get better, stay about the same, or get worse?

The answers to these questions are obviously very specific to company or facility process safety goals based on (1) the particular process hazards and risks that may be present and (2) management priorities.

While assessing current performance seems straightforward, serious process-safety incidents are (hopefully) rare, and therefore performance is typically assessed in terms of conformance to process safety system requirements. But systems and expectations differ, and what is considered excellent performance at one company may not be at another, based on the goals and leading and lagging metrics that have been established. Also, companies may believe they have excellent performance, but the reality could be different when performance is assessed relative to industry standards and regulatory expectations. Both internal and external measurements should be considered when evaluating process safety performance. Facilities must, at a minimum, be aware of industry standards and best practices for comparison, and should benchmark operating results with other facilities and companies whenever possible.

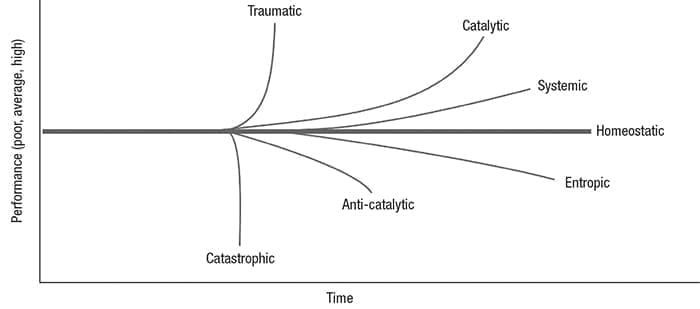

Figure 2. A facility’s process safety performance over time can follow several different pathway scenarios

The second question is more difficult. Several possible pathways or scenarios are shown in Figure 2. The y axis measures performance, where the current status can be generally categorized as high, average or poor. The current status is important because if a company already has excellent performance, it should mainly desire to maintain that high level. If a company has poor performance, it should set goals and provide resources for improvement. From the current status, several performance scenarios are possible:

Entropic. The entropic scenario is characterized by a slow degradation of performance. This is most common where continued attention to process safety performance is not maintained, and often results from either (1) complacency (for example, the absence of recent significant incidents leads to overconfidence that the process safety performance must be adequate), (2) lack of awareness of degradation (for example, no leading metrics or inadequate audits), or (3) competing priorities (such as financial pressures) that prevent appropriate focus on process safety performance. Without continued attention, any system, including a process safety system, will degrade over time as training and human performance expectations lag, equipment continues to age, and other distractions appear. Performance may continue along the entropic path until an event, such as a safety incident or audit, triggers a change of focus.

Homeostatic and systematic. These scenarios reflect continued goal setting to maintain and/or improve performance. Generally, process safety performance is likely to already be good, so the intent is to continue to provide resources to appropriately manage process risks. If performance is not already strong, then these scenarios may indicate insufficient management attention or resources to substantially improve performance until an event again triggers a change in priority for process safety. These scenarios are the most common performance targets for many companies.

Catalytic and anti-catalytic. These scenarios represent triggering events that either lead to rapid improvement or rapid degradation of process safety performance. Typical trigger events may include (1) a near-miss event that raises awareness of possible issues, (2) a change of leadership, such as a new plant manager with a different priority level for safety, (3) an acquisition or merger, especially where there are significant differences in corporate safety culture between the companies, (4) financial considerations due to a change in the overall economy or company cost control, (5) a regulatory change or inspection, (6) internal audits, inspections, or visits by managers that either question or confirm performance, and (7) lawsuits or other legal considerations.

Traumatic and catastrophic. These scenarios represent significant, rapid performance changes typically resulting from serious process incidents at a facility, within the same company, or in a related industry. If a serious incident occurs at the facility, obviously performance will drop immediately, and the disruption and distractions caused by the incident may lead to continued performance issues or even perhaps closure of the facility. If the serious incident occurs at another facility in the company or industry, it may serve as a wake-up call to motivate management to focus immediately on providing resources to improve process safety programs.

Consideration of these two questions — What is our current performance? and What will it be in the future? — is essential for achieving desired performance levels on both absolute (internal) and relative (external) criteria. Achieving excellent performance, of course, does not simply happen. It must be the result of management support of effective process-safety programs, setting annual program goals, and constant measurement and review of performance through appropriate feedback systems. A model of important factors that impact performance is discussed in the next section.

Achieving excellence

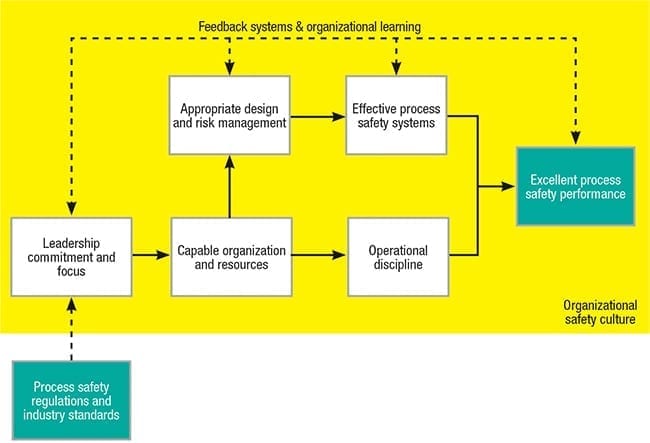

While all aspects of effective process-safety programs are ultimately important, the performance model [2, 8] shown in Figure 3 provides principal program activities that impact performance and indicates how they interact [2]. The key elements of this model are discussed below, with one or more possible actions that companies or facilities can take to help improve performance for each aspect.

Figure 3. The diagram shows a model for process safety performance (adapted from Refs. 2 and 8)

Process-safety regulations and industry standards. Companies must be aware of regulatory requirements and industry best practices. In addition, effective implementation of programs to comply with industry codes and standards (often referred to as “recognized and generally accepted good engineering practices” [RAGAGEPs]), such as consensus standards issued by the American Petroleum Institute, helps ensure equipment is properly designed and maintained. Lack of knowledge of regulations, best practices, and RAGAGEPs will seriously reduce the effectiveness of process safety programs. Knowledge of external information and activities is essential for (1) leveraging organizational capabilities in process safety and (2) ensuring, among other things, proper equipment design and maintenance. The Center for Chemical Process Safety (CCPS), for example, has provided comprehensive guidance on risk-based process safety programs [3] and continues to develop new guidance based on industry best practices. Exposure to process safety literature through selected conferences and journals can also help keep process safety professionals current on new industry developments and practices. Part of organizational learning, discussed below, is to maintain an active external focus to enhance internal activities.

Possible action: Develop systems to ensure proper awareness, access, and use of external process safety regulations and guidance.

Organizational safety culture. The effectiveness of process safety programs and the ability to achieve excellent performance are strongly influenced by the safety culture. Differences in safety culture, often due to conflicting priorities, such as financial or production considerations, can have dramatic effects on safety performance. A poor safety culture, for example, may be able to achieve excellent performance in the short term, but is unlikely to sustain excellent performance over the long term. A good definition of safety culture is [2] “The normal way things are done at a facility, company, or organization, reflected expected organizational values, beliefs, and behaviors, that set the priority, commitment, and resource levels for safety programs and performance.” Characteristics that describe the essential features of safety cultures have been defined [3, 9] and can be used to evaluate strengths and opportunities for improvement. As part of the safety culture, a sense of vulnerability should be maintained to help prevent complacency issues, especially when performance has been strong for a long time. Failing to maintain a sense of vulnerability can directly lead to a mistaken belief that success is routine rather than an outcome that requires continued focus and diligence [ 10]. This is the “entropic” performance scenario shown in Figure 2.

Possible actions: (1) Periodically conduct safety culture assessments. (2) Develop strategies to maintain a sense of vulnerability in personnel at all levels to help prevent complacency.

Leadership commitment and focus. Leadership at a company or facility is both influenced by the safety culture (for example, in setting daily priorities for safety versus production) and is also able to influence the culture (strengthening or weakening the culture over time). As discussed earlier, a change in leadership such as a new plant manager can lead to catalytic or anti-catalytic changes in process safety performance. Leadership necessarily encompasses all levels of management, from a company’s board of directors to first-line supervision [7]. If a shift supervisor is making decisions contrary to guidance from higher levels of management, such as completing certain work tasks in an unsafe manner, then leadership credibility is challenged and the safety culture can degrade. Leadership commitment and focus on process safety are critical for ensuring that resources are provided to help build a capable organization, in terms of financial, personnel and time considerations. Process-safety program policies, goals, metrics, and accountabilities must be established with appropriate resources provided to support excellent performance. Direct leadership involvement in process-safety activities is also essential for building trust and securing employee engagement through visibility and consistent action.

Possible actions: (1) Set appropriate, actionable and measurable process safety improvement goals annually. (2) Ensure that appropriate process safety training is provided to all leadership as part of specific job roles and career advancement criteria.

Capable organization and resources. Company leaders must provide purposeful and sufficient resources for implementing and sustaining effective process-safety programs that support safe, high-quality, and reliable operations. This includes developing internally trained and capable process-safety professionals and others with expertise and knowledge of process operations, process safety regulations and RAGAGEPs to help ensure that process goals can be met. Since it is increasingly difficult for everyone to know everything about all technical areas, appropriate policies and guidance should be documented, training conducted, and networking and mentoring opportunities provided, especially for new or less experienced personnel. In some cases, it is often more effective to involve specialty resources, such as consulting services, for (1) designing effective process safety systems, (2) conducting process safety audits, and (3) assisting with risk management. The decision to develop in-house capabilities versus using specialist consultants and contractors is often based on the risk of the processes that are operated by the company or facility, and other factors, such as company size and resources. Ultimately, process safety must become part of everyone’s job in terms of ensuring that process-safety program goals and requirements are met. A well-defined training strategy should therefore be developed and implemented with refresher training at appropriate intervals to help (1) ensure awareness and understanding of process hazards that may be present and (2) ensure that process safety program requirements for managing these hazards are being met.

Possible actions: (1) Review training strategies to support effective process safety program implementation and performance. (2) Implement an organizational change process to evaluate organizational capabilities and manage personnel changes.

Appropriate design and risk management. Well-designed processes are the starting point for safe and reliable operations and for achieving excellent process safety performance. Process design must generate the desired product of course, but must also be based on identifying, evaluating and managing process hazards and risks. Where possible, process hazards should be eliminated using inherently safer technology approaches [11]. Remaining process hazards must be evaluated using appropriate hazard-evaluation methodologies to help ensure that process hazards are identified and the consequences of administrative and engineering controls have been evaluated. This includes providing safeguards, typically using multiple layers of protection [2, 3]. These evaluations are also used to ensure that process safety systems are designed and implemented as part of effective process safety programs to continually manage process safety activities and performance.

Possible actions: (1) Ensure process safety information that serves as the basis for process design (for example, hazard information, process design basis, equipment design basis) has been properly compiled and is being maintained. (2) Review current risk-management practices to evaluate if hazard evaluations are being properly conducted during all stages of the process lifecycle (for example, initial design to decommissioning).

Effective process safety systems. Process safety systems provide the detailed requirements of the process safety program to help ensure that (1) process hazards have been identified and evaluated before being first introduced into the workplace and (2) process risks are successfully controlled at all times as facility personnel complete their daily work activities. Process safety systems must be designed appropriately based on process hazards and risks that are present, applicable regulatory requirements, and best practice industry guidance. Various approaches have been proposed, ranging from eight management systems [2] to 20 risk-based elements [3]. OSHA (Occupational Safety and Health Administration) process safety management in the U.S. has 14 elements. Core process safety requirements are typically present in these elements, such as operating procedures, training, mechanical integrity, incident investigation and management of change. Proper functioning of these process-safety systems is essential for achieving excellent process safety performance, such that qualified and trained resources should be assigned to lead and monitor individual systems/elements, and specific metrics should be provided to monitor whether or not system requirements are being met. Many leading metrics are associated with proper functioning of these systems, which provide early warning of both current and future performance problems.

Possible action: Ensure appropriate leading and lagging metrics are being monitored to review process safety system performance.

Operational discipline (OD). Process safety systems only work as intended if personnel are actually following them; even highly trained people occasionally make mistakes. The reality is that human error should be anticipated, and appropriate systems and safeguards should be provided to make sure errors do not lead to serious injuries and other consequences, especially if work tasks include higher-risk activities involving significant process hazards. Operational discipline is used to describe human behavior in following required systems and procedures correctly, every time, to consistently achieve safer and more reliable operations. Developing an OD program [2, 12] intended to support day-to-day awareness and commitment by all company personnel can help (1) minimize the potential for human error, (2) ensure process safety program requirements are rigorously followed, and (3) support excellent process safety performance. An OD program focuses on both organizational and personal OD to (1) help company or facility management develop the programs and work environment to support strong operational discipline and (2) provide resources for supporting OD improvement efforts. Personal OD programs are based on ensuring personnel at all levels have the knowledge, commitment, and awareness to complete their individual work activities correctly and safely every time.

Possible action: Identify OD improvement opportunities based on implementing an OD program or conducting additional OD evaluations as part of an existing OD program.

Feedback systems and organizational learning. Methods to monitor process-safety program effectiveness using both leading and lagging metrics are essential for achieving high performance [2,3]. Without appropriate program feedback, warning signs of problems may be missed and learning opportunities for improving performance can be lost. Ensuring that the correct factors are measured and evaluated, based on process-safety program goals, provides information on the current performance level (poor, average, high) and trend direction (getting better or worse). Metrics by themselves are of little use unless they are acted upon, by identifying strengths and weaknesses and initiating specific improvement opportunities. Learning from experience is a common process-safety theme, and the use of organizational learning approaches to collect, analyze, share and retain critical process-safety information helps promote sensitivity to operations, a sense of vulnerability, and knowledge of past problems and successes [2]. Developing a process safety learning plan, based on learning goals, competency needs, information collection, and retention of knowledge can strengthen process safety programs and performance over time.

Possible action: Develop a process safety learning plan.

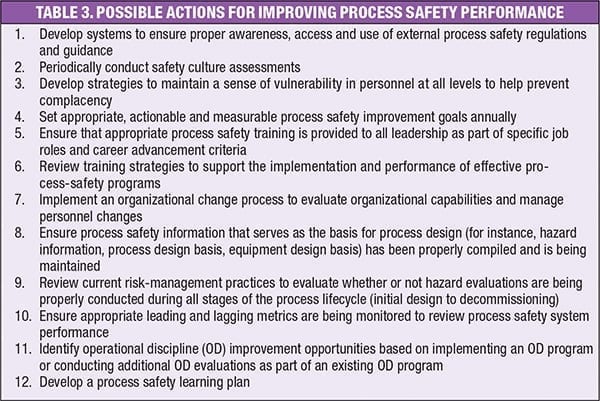

The possible actions discussed for improving process safety performance are summarized in Table 3. Many additional actions are possible, of course, based on specific facility goals, current performance, and identified improvement opportunities.

Concluding remarks

Are you happy with your process safety performance? What is the level of current performance relative to company expectations and industry standards? Will performance be better in the future? What specific approaches are being taken to make sure performance remains excellent or improves? Sustained excellent process safety performance is possible, but requires sustained commitment and resources to implement and improve effective process safety programs. Past success will not ensure future success, as competing priorities and other challenges will always be present. The technical knowledge and capabilities to implement and maintain robust process-safety programs and achieve high levels of performance are readily available, based on process safety regulations, industry guidance, and resources such as RAGAGEPs. The actions discussed here for helping to improve process safety performance are important, but ultimately deciding to set appropriate performance goals and evaluate specific facility or company opportunities for improving performance will increase the likelihood of process safety success.

Edited by Scott Jenkins

References

1. Klein, J.A., Two Centuries of Process Safety at DuPont, Process Safety Progress, vol. 28, pp. 114–123, 2009.

2. Klein, J.A. and B. K. Vaughen, “Process Safety: Key Concepts and Practical Approaches,” CRC Press, 2017.

3. Center for Chemical Process Safety, “Guidelines for Risk-Based Process Safety,” John Wiley & Sons, 2007.

4. Kletz, T., “Lessons From Disaster: How Organizations Have No Memory and Accidents Recur,” Gulf Professional Publishing, 1993.

5. Hendershot, D.C., Process Safety Management — You Can’t Get It Right Without a Good Safety Culture, Process Safety Progress, vol. 31, pp. 2–5, 2012.

6. U.S. Chemical Safety Board, “Refinery Explosion and Fire,” Report No. 2005-04-I-TX, 2007.

7. “The Report of the BP U.S. Refineries Independent Safety Review Panel,” 2007.

8. Klein, J.A. and J.R. Thompson, Improving Process Safety Performance, paper at Global Congress on Process Safety, Austin, Texas, 2015.

9. Center for Chemical Process Safety, “Essential Practices for Developing, Strengthening and Implementing Process Safety Culture,” John Wiley & Sons, 2018.

10. Klein, J.A. and S. Dharmavaram, Improving the Performance of Established PSM Programs, Process Safety Progress, vol. 31, pp. 261–265, 2012.

11. Center for Chemical Process Safety, “Inherently Safer Chemical Processes: A Life Cycle Approach,” Second Edition, John Wiley & Sons, 2009.

12. Klein, J.A. and E. M. Francisco, Focus on Personal Operational Discipline to Get Work Done Right, Process Safety Progress, vol. 31, pp. 100–104, 2012.

Author

James A. Klein, CCSPC, CSPA has over 39 years of experience in process safety, engineering, and research. He joined ABSG Consulting Inc. (ABS Group, 1701 City Plaza Drive, Spring, TX 77389; Email: [email protected]; Website: www.abs-group.com) in 2013 as a senior process safety consultant. Prior to that, he was process safety management co-lead for North America operations at DuPont. He is the co-author of “Process Safety: Key Concepts and Practical Approaches,” published by CRC Press, and has developed over 50 publications, conference presentations, and university talks. He holds a B.S. degree in chemical engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), an M.S. degree in chemical engineering from Drexel University, and an M.S. degree in management of technology from the University of Minnesota.

James A. Klein, CCSPC, CSPA has over 39 years of experience in process safety, engineering, and research. He joined ABSG Consulting Inc. (ABS Group, 1701 City Plaza Drive, Spring, TX 77389; Email: [email protected]; Website: www.abs-group.com) in 2013 as a senior process safety consultant. Prior to that, he was process safety management co-lead for North America operations at DuPont. He is the co-author of “Process Safety: Key Concepts and Practical Approaches,” published by CRC Press, and has developed over 50 publications, conference presentations, and university talks. He holds a B.S. degree in chemical engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), an M.S. degree in chemical engineering from Drexel University, and an M.S. degree in management of technology from the University of Minnesota.